Key Points:

- The European Commission is consulting the semiconductor industry regarding China’s legacy chip production.

- Two voluntary surveys will target the chip industry. The EU has imposed tariffs up to 37.6% on Chinese electric vehicles, signaling a tougher stance.

- China heavily invests in legacy chip production to reduce foreign dependency, raising Western concerns about oversupply.

- European tech firms face a mixed scenario with increasing Chinese competition and ongoing business interests in China.

According to sources familiar with the matter, the European Commission has initiated consultations with the semiconductor industry to gather perspectives on China’s increased production of older-generation computer chips. This feedback collection precedes two voluntary surveys targeted at the chip industry and major industrial firms that utilize chips, scheduled for completion in September.

A Commission spokesperson confirmed the targeted industry consultation to assess the use of legacy chips in supply chains. In an emailed response, the spokesperson mentioned that the EU and US might collaborate on measures to address dependencies or distortionary effects stemming from China’s chip production.

The outcome of this study remains uncertain, but it underscores escalating tensions between Brussels and Beijing as the EU seeks to shield its industries from Chinese competition. Recently, the Commission imposed provisional tariffs of up to 37.6% on Chinese electric vehicles, signaling a tougher stance towards Beijing.

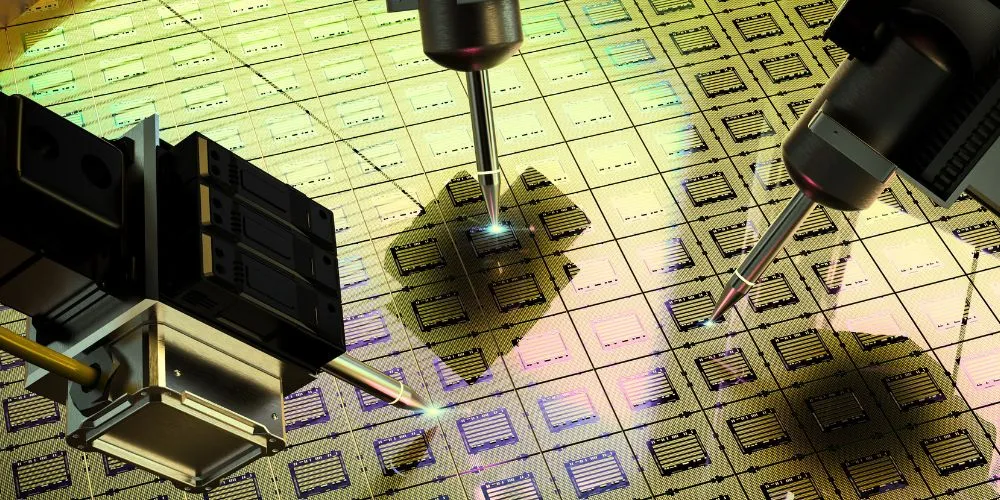

Chinese industry, supported by state subsidies, is heavily investing in expanding legacy chip production. This investment is partly driven by U.S.-led restrictions that limit China’s access to more advanced chip technologies. While this expansion reduces China’s short-term dependence on foreign chips, Western governments are concerned about potential long-term implications, including oversupply of these essential components.

In April, EU antitrust chief Margrethe Vestager hinted at a potential investigation into legacy chips following a meeting with U.S. officials, including Commerce Secretary Gina Raimundo. Additionally, the Commission published a 712-page report detailing the Chinese government’s support to domestic firms across multiple sectors, including semiconductors, telecom equipment, and renewable energy. Trade analysts viewed this report as an indication that Brussels might initiate more cases against Chinese practices.

The upcoming chip-focused surveys are intended as fact-finding missions and are broader in scope than a security-focused survey conducted by the U.S. Department of Commerce. The Commission is seeking information on where industrial firms source their chips, details on chip firms’ products and pricing, and estimates of similar data from their competitors, including Chinese firms.

China’s legacy chip production represents a significant revenue stream for European tech giants like ASML that offsets U.S.-led export restrictions on advanced technology. The scenario is complex for chipmakers such as Germany’s Infineon, France’s STMicroelectronics, and the Netherlands’ NXP. These companies, key players in automotive and electrical infrastructure chips, face increasing Chinese competition but also maintain substantial business interests in China.

European industrial, aerospace, automotive, health-tech, and energy firms may hesitate to disclose their use of Chinese legacy chips, often due to the complex, multi-step nature of chip production and packaging. German carmakers, in particular, oppose tariffs on Chinese EVs, given their significant market in China. They have diversified their chip suppliers to include sources within and outside China and Taiwan, especially after facing costly shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic.