Key Points

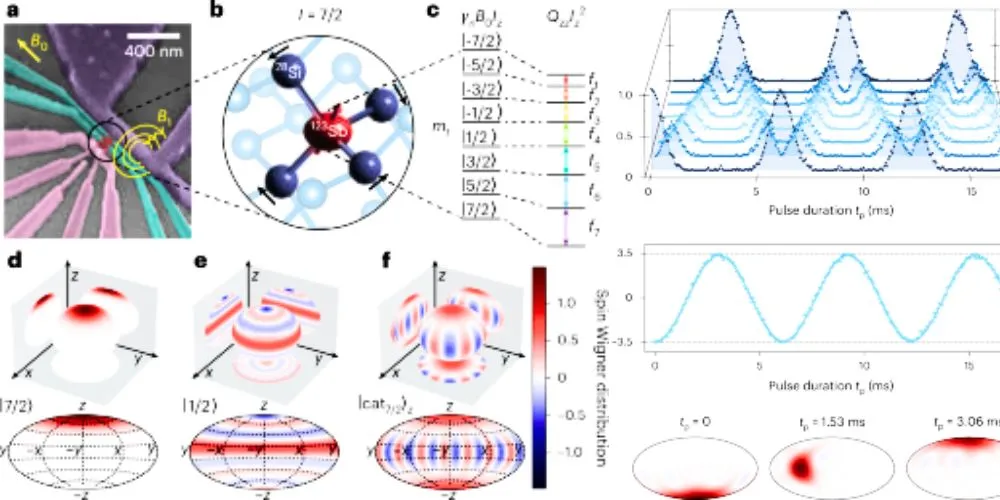

- UNSW engineers realized Schrödinger’s cat concept with an antimony atom.

- Antimony’s eight spin directions provide resilience against quantum errors.

- The atom was embedded in a silicon chip, allowing scalable technology.

- The breakthrough enhances error detection and correction in quantum computing.

UNSW engineers have brought a famed quantum thought experiment into reality, offering a groundbreaking approach to quantum computing. The research focuses on a quantum phenomenon akin to Schrödinger’s cat, where an object exists in multiple states simultaneously. The study, published in Nature Physics, demonstrates a way to strengthen quantum error correction, a key hurdle in creating functional quantum computers.

The experiment centered on an atom of antimony, a complex element compared to standard qubits. Unlike traditional quantum bits, which have two spin states—up and down—the antimony atom possesses eight spin directions. This complexity creates a superposition of states separated by multiple quantum levels, making it far more error-resistant. A single disruption cannot scramble the quantum code, requiring seven consecutive errors to change the logical state of the system.

Lead author Xi Yu likened this resilience to the metaphor of a cat with multiple lives. Encoding quantum information in these “macroscopic” spin states introduces significant room for error, allowing scientists to detect and correct disruptions before they accumulate. Co-author Benjamin Wilhelm emphasized that this innovation addresses the fragility of quantum information, enabling more stable computations.

The antimony atom was embedded in a silicon chip designed to access the quantum state of a single atom. Fabricated by UNSW’s Dr. Danielle Holmes and her team, in collaboration with the University of Melbourne, the chip leverages existing silicon technology. This approach could scale to modern computing methods, offering a pathway to practical quantum devices.

This breakthrough holds promise for more robust quantum computations, where errors are detected early and corrected in real time. Prof. Andrea Morello, the team leader, described this advance as a step closer to the “Holy Grail” of quantum error correction. The project also showcased international collaboration, with contributions from UNSW, Sandia National Laboratories, NASA Ames, and the University of Calgary.