Key Points:

- Campfire flares and small eruptions on the sun’s surface were discovered in 2020 by the Solar Orbiter probe.

- Solar physicist Navdeep Panesar and her team observed that 80% of campfire flares were preceded by dark structures composed of cool plasma.

- These findings suggest that campfire flares, coronal jets, and other solar eruptions may share similar underlying mechanisms.

- Campfire flares heat the sun’s million-degree atmosphere, known as the corona, posing a longstanding puzzle in solar physics.

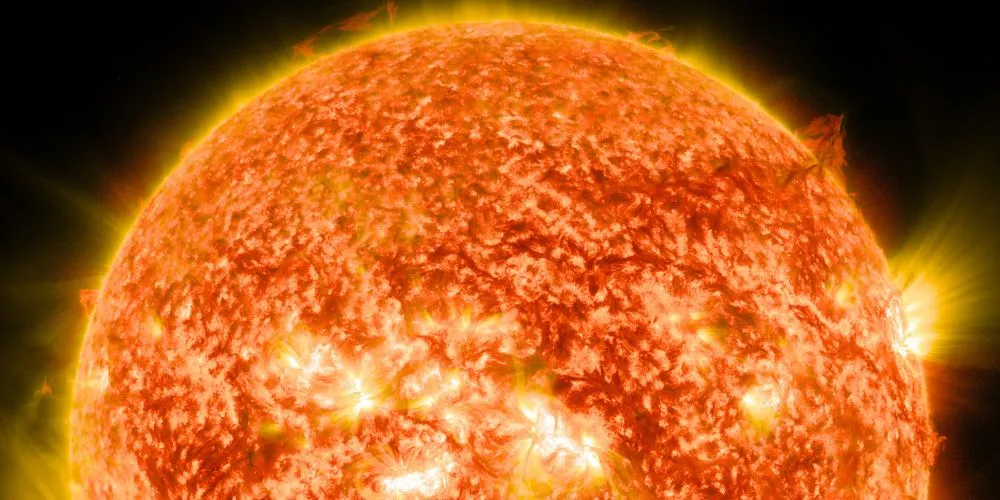

Recent discoveries shed light on the elusive phenomenon of campfire flares erupting on the sun’s surface, offering new insights into their underlying mechanisms and potential implications for solar physics. These miniature eruptions, first observed in 2020 by the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter probe, have puzzled scientists due to their small size and distinctive characteristics.

Solar physicist Navdeep Panesar and her team from Lockheed Martin Solar and Astrophysics Laboratory in Palo Alto, Calif., analyzed close-up images captured by the Solar Orbiter to investigate the origins of campfire flares. Their research, presented at the Triennial Earth-Sun Summit, revealed intriguing patterns preceding the emergence of these diminutive bursts of ultraviolet light.

The team observed that approximately 80% of campfire flares were preceded by the formation of dark structures composed of cool plasma. As this cool plasma rises, a brightening phenomenon occurs underneath it, eventually culminating in the appearance of a campfire flare. Interestingly, similar cool plasma structures have been observed preceding other solar explosions, such as coronal jets.

These findings suggest that the mechanisms underlying campfire flares, coronal jets, and other solar eruptions may be more interconnected than previously thought. Like larger solar flares and coronal mass ejections, campfire flares are believed to be triggered by the complex interplay of magnetic fields on the sun’s surface.

The intense heat of campfire flares, ranging from half a million to 2.5 million degrees Celsius, has intrigued scientists. They heat the sun’s million-degree atmosphere, known as the corona. This phenomenon presents a longstanding puzzle in solar physics: Why is the corona significantly hotter than the sun’s surface, which reaches temperatures of only 5500°C?

While the precise mechanisms driving campfire flares remain elusive, these recent observations provide valuable clues for unraveling their mysteries. By studying these miniature eruptions, scientists hope to understand better the sun’s complex dynamics and the fundamental processes shaping its behavior.