Materials define human history. From the Stone Age to the Bronze Age, the Iron Age, and finally the Silicon Age, our ability to discover, harness, and engineer new substances has been the primary engine of technological and societal progress. Yet, for millennia, this process has been painstakingly slow—a frustrating game of intuition, serendipity, and brute-force trial and error. Today, we stand at the precipice of a new epoch, one where this paradigm is being completely upended. The Artificial Intelligence (AI) revolution is here, and it is transforming materials science from an art of patient discovery into a science of rapid, predictive design.

This shift is not merely an incremental improvement; it is a fundamental change in how we invent the physical world around us. AI is compressing development timelines from decades into months, unlocking a combinatorial universe of materials previously unimaginable, and creating a direct pipeline from a computational idea to a real-world application. This acceleration is poised to deliver solutions to some of humanity’s most pressing challenges, from climate change and energy storage to personalized medicine and space exploration.

The Old Paradigm: A Search for a Needle in an Infinite Haystack

To appreciate the magnitude of the AI revolution, one must first understand the monumental challenge of traditional materials discovery. The classic approach, often called the “Edisonian method,” involves researchers formulating a hypothesis, synthesizing a small number of candidate materials, and then meticulously testing their properties. While this method has yielded wonders like Teflon, Kevlar, and Gorilla Glass, it is profoundly inefficient.

The core problem is one of combinatorial explosion. The number of possible combinations of elements in the periodic table to form stable compounds is astronomically large. Even when considering simple three- or four-element compounds, the potential candidates number in the billions.

Exploring this vast “materials space” through physical experimentation is like trying to find a single, specific grain of sand on all the beaches of the world. Consequently, discovering a commercially viable new material has historically taken an average of 10 to 20 years and cost hundreds of millions of dollars. We have been limited not by our imagination, but by our physical capacity to search.

The AI Toolkit: How AI is Changing the Game

AI, and specifically machine learning (ML), provides a powerful set of tools to navigate this immense materials space intelligently. Instead of wandering blindly, scientists can now use AI to build detailed maps, identify promising regions, and predict the properties of materials before a single atom is synthesized in a lab.

Predictive Modeling: Learning from the Past

At its simplest, AI excels at pattern recognition. Researchers have spent decades accumulating vast databases of known materials, cataloging their atomic structures and measured properties (e.g., conductivity, strength, melting point). Machine learning models can be trained on this data to learn the complex, quantum-level relationships between a material’s structure and its function.

Once trained, these models can perform “forward prediction.” A scientist can propose a hypothetical atomic structure, and the AI will predict its properties with remarkable accuracy in seconds. This task would normally require weeks of synthesis and characterization. This allows for the rapid screening of millions of virtual candidates, instantly filtering out unpromising options and highlighting a small, manageable set of high-potential materials for further investigation.

Generative AI and Inverse Design: Designing Materials on Demand

While predictive modeling is powerful, the true game-changer is inverse design. This flips the traditional process on its head. Instead of asking, “What are the properties of this material I designed?”, scientists can now ask, “What material has the exact properties I need?”

This is where generative AI models, similar to those that create art (DALL-E) or text (GPT-4), come into play. Techniques like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) can be trained on the “language” of crystal structures.

Scientists can then provide a set of desired target properties—for instance, “highly conductive, transparent, flexible, and made from earth-abundant elements”—and the generative model will invent novel, physically plausible atomic structures that meet those criteria. It is the ultimate form of creative engineering, allowing us to design materials tailored for a specific purpose.

Natural Language Processing (NLP): Unlocking Decades of Hidden Knowledge

The world’s scientific knowledge is largely trapped in unstructured text within millions of research papers. Natural Language Processing (NLP) models can read, comprehend, and synthesize this massive corpus of literature at superhuman speed. These AI tools can scan decades of publications to extract crucial information, such as synthesis parameters (“bake at 800°C for 12 hours”), material properties, and experimental setups.

This process not only builds more comprehensive databases for training other AI models but can also uncover hidden correlations and forgotten recipes that no single human researcher could ever hope to find.

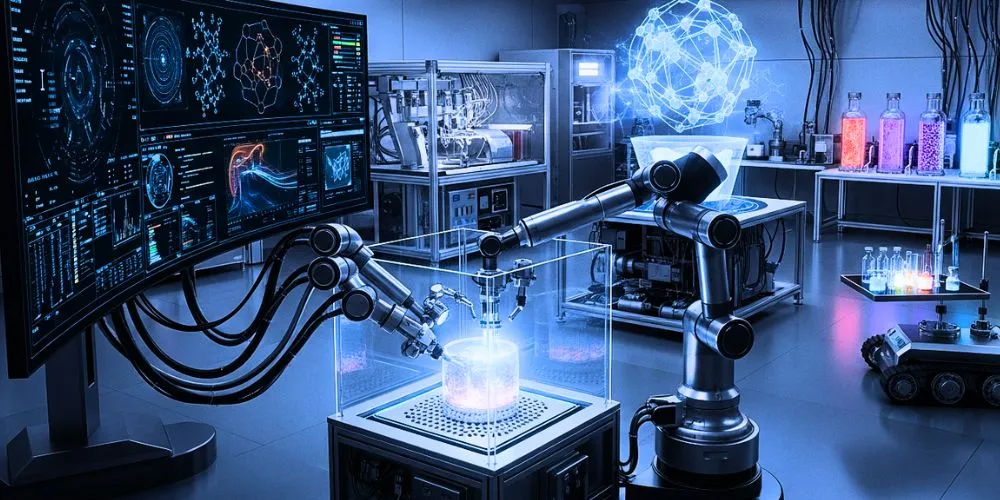

From Code to Creation: The Rise of the Autonomous Lab

The most exciting frontier in this field is the integration of AI with robotics, creating what are known as “autonomous labs” or “self-driving laboratories.” These facilities close the loop between digital prediction and physical reality, creating a virtuous cycle of accelerated discovery.

The workflow is a marvel of efficiency:

- Hypothesize: An AI model proposes a list of the most promising new material candidates to achieve a specific goal.

- Synthesize: A robotic system automatically measures out the precursors, mixes them, and performs the necessary chemical reactions to create a small sample of the material.

- Test: Another set of automated instruments characterizes the new material’s properties—its crystal structure, electrical conductivity, optical absorption, etc.

- Learn: The experimental results are immediately fed back into the central AI model.

- Iterate: The AI updates its understanding based on the new data—learning from both its successes and failures—and intelligently selects the next, even more promising material to synthesize.

This closed-loop process can run 24/7, performing hundreds of experiments per day with a level of precision and reproducibility that humans cannot match. What once took a PhD student months of painstaking work can now be accomplished in a single afternoon.

Real-World Impact: AI-Discovered Materials in Action

This is not science fiction. AI-driven materials discovery is already delivering tangible results across critical industries.

Energy and Batteries

The quest for better batteries is a defining challenge of our time. In 2023, researchers at Google DeepMind used AI to predict the structure and stability of over 2.2 million new crystal structures, including nearly 400,000 stable materials that could be candidates for next-generation technologies. This work massively expanded the known landscape of stable materials. Other projects are using AI to discover new solid-state electrolytes for safer, more energy-dense batteries, potentially revolutionizing electric vehicles and grid-scale energy storage.

Sustainability and Green Tech

AI is accelerating the discovery of new catalysts that can efficiently capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere or convert waste products into valuable chemicals. It is also being used to design novel perovskite materials for more efficient and stable solar cells and to invent new biodegradable polymers to combat plastic pollution.

Aerospace and Manufacturing

The demand for lighter, stronger, and more heat-resistant materials is relentless. AI is being used to design complex metal alloys, known as high-entropy alloys, that possess unprecedented combinations of strength and durability for jet engines and spacecraft. By simulating thousands of potential compositions, AI can pinpoint optimal formulations that would be impossible to find through traditional experimentation.

The Challenges and the Road Ahead

Despite the immense promise, the path to a fully AI-driven materials future is not without its obstacles.

- Data Quality and Scarcity: AI models are only as good as the data they are trained on. In many niche areas of materials science, high-quality, standardized experimental data is still scarce, limiting the predictive power of AI.

- The “Black Box” Problem: Many advanced AI models, particularly deep neural networks, are notoriously opaque. They may predict a revolutionary new material, but scientists often struggle to understand why the model made that choice, hindering scientific intuition and trust. Developing more “explainable AI” (XAI) is a critical area of research.

- Bridging the Simulation-to-Reality Gap: A material that looks perfect in a computer simulation may be incredibly difficult or impossible to synthesize in the real world. Improving the integration between predictive models and the practical constraints of chemistry and physics is essential.

Conclusion

The fusion of artificial intelligence and materials science marks a pivotal moment in human innovation. We are moving from an era of chance discovery to one of intentional design. AI is not replacing human scientists; it is augmenting them, freeing them from tedious experimentation to focus on higher-level creative thinking and problem-solving. It serves as an infinitely knowledgeable, tireless collaborator that can explore possibilities at a scale and speed previously unimaginable.

As these AI tools become more powerful and autonomous labs more widespread, we are fast approaching a future of “materials on demand”—where an engineer facing a specific challenge can simply define the required properties and have an AI design and guide the creation of a bespoke material to solve it. This capability will unlock innovations we can barely envision today, heralding a new materials age that will redefine our world.