Key Points

- Chinese scientists have captured the first direct evidence of the “Migdal effect,” a phenomenon predicted in 1939.

- The effect occurs when a jolt to an atomic nucleus causes it to eject an electron.

- The Migdal effect could be the key to detecting “light dark matter.”

- The finding is a breakthrough in the nearly century-long search for dark matter.

In a breakthrough, a team of Chinese scientists has captured the first direct evidence of a long-theorized “ghost effect” in atomic physics. The discovery, which confirms a prediction made nearly 90 years ago, could be the key to finally finding dark matter, the mysterious, invisible substance that makes up most of the universe.

The effect, known as the “Migdal effect,” was first predicted in 1939. It says that when an atom’s nucleus is suddenly jolted, for example, by a collision with a dark matter particle, it can cause one of the atom’s own electrons to be ejected. For decades, this has been purely a theoretical idea, as the effect is incredibly small and hard to detect.

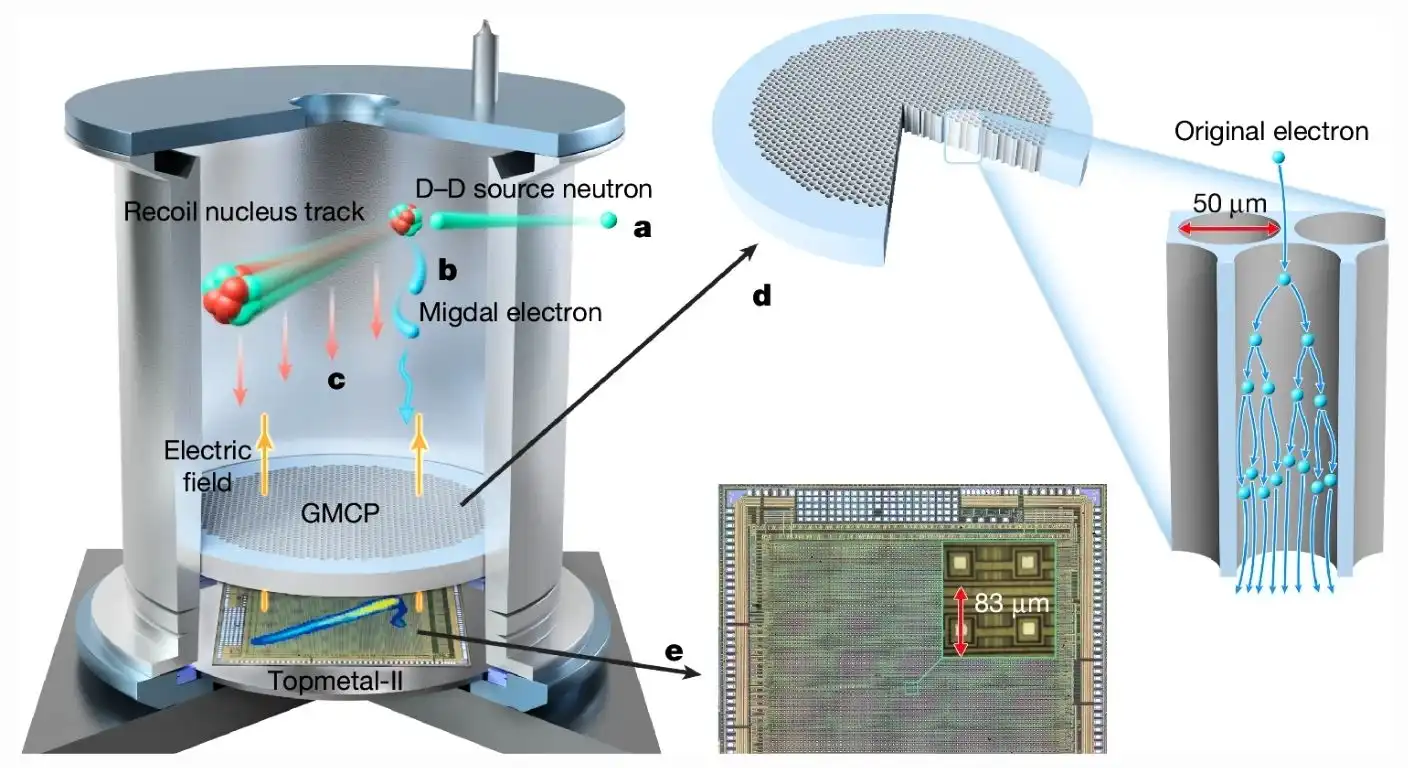

To capture it, the Chinese research team developed a special “atomic camera,” a super-sensitive gas detector that can track the path of a single atom and the electron it releases.

By bombarding gas molecules with neutrons and sifting through over 800,000 potential events, they found six clear signals that showed the tell-tale signature of the Migdal effect: two particle tracks, one from the recoiling nucleus and one from the ejected electron, both starting from the same point.

This discovery is a huge deal for the search for dark matter. For years, scientists have been looking for heavy, dark matter particles but have come up empty-handed. Now, the focus is shifting to “light dark matter,” which is much harder to detect because it doesn’t give the atomic nucleus much of a kick.

The Migdal effect changes all of that. It essentially turns a tiny, almost imperceptible jolt into a much larger, more easily measurable electronic signal. “With the Migdal effect, once an electron is ejected, our detector can, in theory, capture 100% of its energy,” said one of the lead researchers.

This work fills a long-standing gap in experimental physics and represents a crucial first step toward using this “ghost effect” to hunt for the universe’s most elusive substance.

Source: Nature (2026).