The world has a plastic problem. Since the 1950s, humanity has produced over 8.3 billion tons of plastic. Of that staggering amount, only about 9% has been recycled. The vast majority sits in landfills, chokes our oceans, or breaks down into microplastics that infiltrate the food chain.

Traditional recycling—known as mechanical recycling—is a flawed system. It involves washing, shredding, and melting plastic. However, every time plastic is melted, its quality degrades. A clear plastic bottle becomes a murky carpet fiber and eventually becomes unrecyclable waste. It is a downward spiral.

But what if we could recycle plastic infinitely? What if we could break it down into its original molecular building blocks and rebuild it, good as new, forever?

This is the promise of Enzymatic Recycling. By harnessing the power of biology—specifically, engineered enzymes that “eat” plastic—scientists are developing a technology that could close the loop on the circular economy and solve one of the greatest environmental challenges of our time.

This comprehensive guide explores the science of enzymatic recycling, the breakthrough organisms making it possible, and the industrial race to scale this biological solution.

The Flaw in Mechanical Recycling

To understand why enzymatic recycling is revolutionary, we must first understand why our current system is failing.

Mechanical recycling is a physical process.

- Contamination: You throw a dirty yogurt cup in the bin. The food residue, the paper label, and the glue are contaminants.

- Downcycling: When plastics are melted together, the long polymer chains that give plastic its strength and clarity are shortened. This makes the recycled material weaker and yellower.

- Limitations: You cannot turn a colored shampoo bottle back into a clear water bottle. You can only turn it into a park bench or a flower pot. Eventually, it hits the end of the line.

We need a chemical reset button.

How Enzymatic Recycling Works: The Biological Scissors

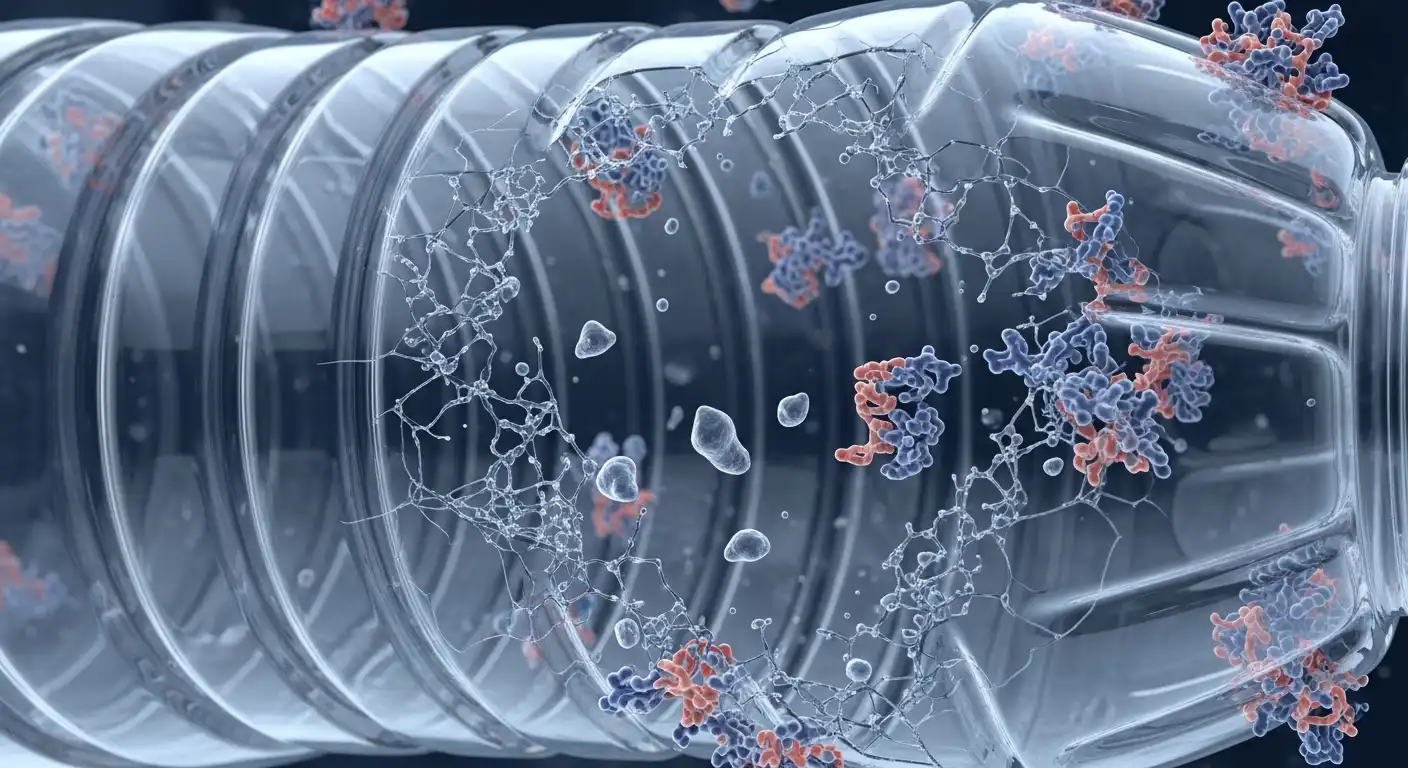

Enzymatic recycling is a form of Chemical Recycling, but instead of using harsh heat or toxic solvents, it uses proteins (enzymes) as catalysts.

The Chemistry of Depolymerization

Plastics are polymers—long chains of repeating units called monomers. Imagine a Lego castle (the plastic bottle) made of thousands of individual Lego bricks (monomers).

- Mechanical recycling smashes the castle into chunks and glues them back together.

- Enzymatic recycling takes the castle apart, brick by brick.

The enzymes act as “molecular scissors.” They target specific chemical bonds in the polymer chain and snip them. This process, called depolymerization, reduces the plastic back to its virgin monomers (such as terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol for PET).

These monomers can then be purified and repolymerized to create brand-new plastic indistinguishable from plastic made from oil. It can be recycled infinitely with zero loss of quality.

The Discovery of the Plastic-Eating Bacteria

The story of enzymatic recycling began in a pile of trash. In 2016, researchers at the Kyoto Institute of Technology were sifting through samples from a bottle recycling plant in Japan. They discovered a bacterium, Ideonella sakaiensis, that had evolved a unique ability: it could eat Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET), the world’s most common plastic used in soda bottles and clothing.

The bacteria produced two specific enzymes:

- PETase: This enzyme attacks the hard plastic surface, breaking it down into smaller intermediate chemicals.

- MHETase: This enzyme breaks those intermediates down further into the basic monomers the bacteria use for energy.

This discovery was a bombshell. Nature had evolved a solution to a man-made problem in just 70 years.

Engineering the Super-Enzyme

While Ideonella sakaiensis was a miracle, it was a slow one. In nature, it took weeks to break down a thin film of plastic. That is too slow for industrial recycling.

Scientists went to work “supercharging” the enzyme.

- Directed Evolution: Researchers at the University of Portsmouth and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) used X-ray technology to map the 3D structure of the PETase enzyme. They then tweaked its DNA, engineering a mutant version that was 20% faster.

- The Cocktail: In 2020, they went further. They physically linked the PETase and MHETase enzymes together to create a “super-enzyme” cocktail. This chimeric protein could break down plastic six times faster than the original bacterium.

Today, companies utilize AI and machine learning to test thousands of enzyme variations, creating proteins that can survive high industrial temperatures and chew through plastic in hours, not weeks.

The Pioneer Companies: Moving from Lab to Factory

This is no longer just a science experiment. Enzymatic recycling is entering the commercial phase, led by a few pioneering biotech firms.

Carbios (France)

Carbios is the current leader in the field. They have developed an enzyme that can break down 97% of PET plastic in just 16 hours.

- The Proof: In 2021, they produced the world’s first food-grade PET bottles made entirely from enzymatically recycled plastic.

- Partnerships: They have signed agreements with giants like L’Oréal, Nestlé Waters, PepsiCo, and Suntory Beverage to supply recycled plastic for their packaging. They are currently building the world’s first industrial-scale enzymatic recycling plant.

Samsara Eco (Australia)

Samsara Eco uses “enzyme libraries” to find proteins that can attack different types of plastics, not just PET. They recently partnered with Lululemon to create the world’s first yoga mats and apparel made from enzymatically recycled nylon and polyester. This tackles the massive problem of “fast fashion” waste.

Protein Evolution (USA)

Backed by fashion designer Stella McCartney, this company uses AI to design enzymes specifically for textile recycling. Their goal is to take a mixed-fabric shirt (cotton/polyester blend), dissolve the polyester, and leave the cotton intact, solving the textile separation problem that plagues traditional recycling.

The Advantages of Bio-Recycling

Why invest billions in enzymes? The benefits are transformative.

Infinite Circularity

As mentioned, the quality does not degrade. We can stop drilling for new oil to make plastic because the existing plastic becomes a permanent resource.

Handling Mixed Waste

Mechanical recycling requires pure waste streams. A blue bottle must be separated from a clear bottle. Enzymatic recycling is more forgiving. The enzyme only targets the specific polymer bonds. You can throw a dirty, multi-colored pile of plastic into the vat; the enzyme will eat the PET and leave the dye and dirt behind as sludge, which is easily filtered out.

Lower Energy Footprint

Chemical recycling (using heat/solvents) requires high temperatures and pressures, consuming lots of energy. Enzymatic recycling happens at relatively mild temperatures (60-70°C), resulting in a significantly lower carbon footprint.

The Challenges: Why Isn’t It Everywhere?

Despite the promise, hurdles remain before enzymatic recycling becomes the global standard.

Cost

Currently, virgin plastic (made from oil) is incredibly cheap. Enzymatic recycling is a high-tech process involving bioreactors and protein engineering. The recycled monomers are currently more expensive than virgin plastic. For this to scale, either the cost of the technology must drop, or governments must impose taxes on virgin plastic to level the playing field.

Speed and Scale

Breaking down a few grams of plastic in a beaker is easy. Processing millions of tons of waste requires massive infrastructure. Breeding enough bacteria to produce tons of enzymes is a logistical challenge (though similar to brewing beer).

Not All Plastics

Currently, enzymatic recycling works brilliantly for PET (bottles/clothing) and increasingly for Polyurethane (foam) and Polyamide (nylon). However, the “Holy Grail” remains Polyethylene (PE) and Polypropylene (PP)—the plastics used in bags, films, and caps. These plastics have very strong carbon-carbon bonds that are extremely difficult for enzymes to cut. While research is ongoing (using wax worm enzymes), a commercial solution for plastic bags is still years away.

The Future: A Bioremediation Revolution

Enzymatic recycling represents a shift in how we view waste. We are moving from a mechanical view (smashing things) to a biological view (digesting things).

Future applications go beyond the factory.

- Landfill Mining: We could spray enzyme cocktails onto existing landfills to accelerate the breakdown of decades-old waste.

- Microplastic Filters: Washing machines could be fitted with enzyme filters that digest the microfibers shed by our clothes before they enter the water system.

Conclusion

Enzymatic recycling is the missing link in the circular economy. It bridges the gap between the convenience of plastic and the limits of our planet. While it is not an excuse to continue producing unlimited waste, it offers a pragmatic, scalable solution to manage the material that defines our age.

By partnering with nature—by hacking the very code of life to clean up our mess—we are turning the problem of plastic pollution into the solution of sustainable manufacturing. The bacteria have shown us the way; now we just need to build the factories.