Key Points

- Würzburg neuroscientists used machine learning to study brain connections and intelligence.

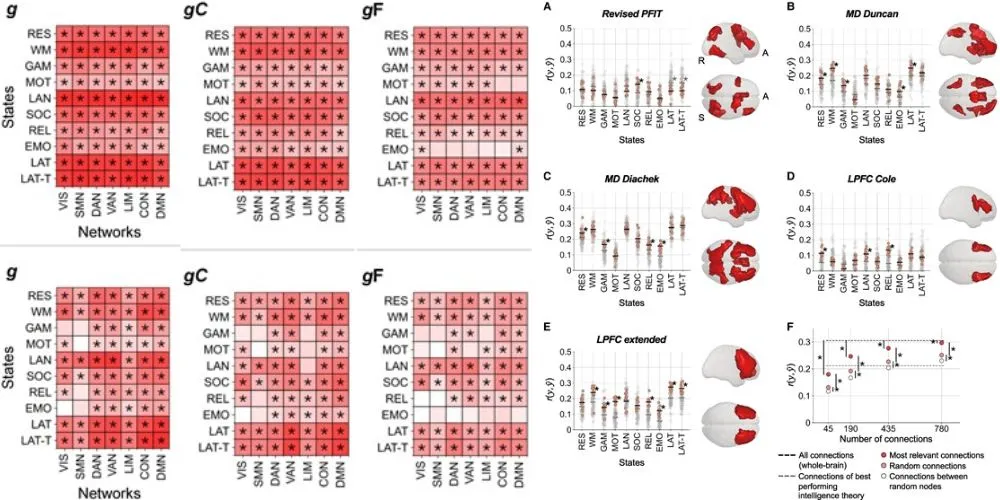

- Data from over 800 participants showed brain-wide connections as key predictors of intelligence.

- Three intelligence types were analyzed: fluid, crystallized, and general intelligence. General intelligence achieved the highest predictive performance.

- Results challenge traditional theories focused on specific brain areas like the prefrontal cortex.

A recent study by neuroscientists from Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg (JMU) employs innovative machine-learning techniques to shed new light on the intricate relationship between brain connectivity and intelligence. Researchers Jonas Thiele and Kirsten Hilger, who lead the “Networks of Behavior and Cognition” group at JMU, published their findings in PNAS Nexus.

The study explored how patterns of communication between brain regions, observed through functional MRI (fMRI), correlate with individual intelligence scores. Analyzing data from over 800 participants, the team examined brain activity at rest and during task performance. Unlike earlier studies, which focused on predicting intelligence scores with limited accuracy, the Würzburg researchers sought a deeper understanding of the neural processes underlying intelligence.

Their findings distinguished three forms of intelligence: fluid intelligence, associated with problem-solving and pattern recognition; crystallized intelligence, encompassing knowledge and skills gained through life experience; and general intelligence, combining the two. General intelligence yielded the most accurate predictions, followed by crystallized and fluid intelligence.

The study revealed that intelligence is influenced by brain-wide connections rather than isolated regions like the prefrontal cortex, as traditionally assumed. Randomly selected brain connections and their distribution across the entire brain contributed significantly to predictive accuracy, highlighting the global nature of intelligence. Adding complementary connections to established neurocognitive models improved the predictive results, suggesting that intelligence depends on interactions across diverse brain regions.

These findings challenge existing theories and point to unexplored dimensions of intelligence. Hilger hopes the study will inspire future research to prioritize interpretability and broaden the conceptual understanding of cognition.