Key Points

- Malaria parasites move in a right-handed, corkscrew pattern.

- The spiral motion helps the pathogen drill through body tissue.

- Researchers used a synthetic gel to mimic human flesh for testing.

- An asymmetrical shape at the front of the cell causes the cell to turn.

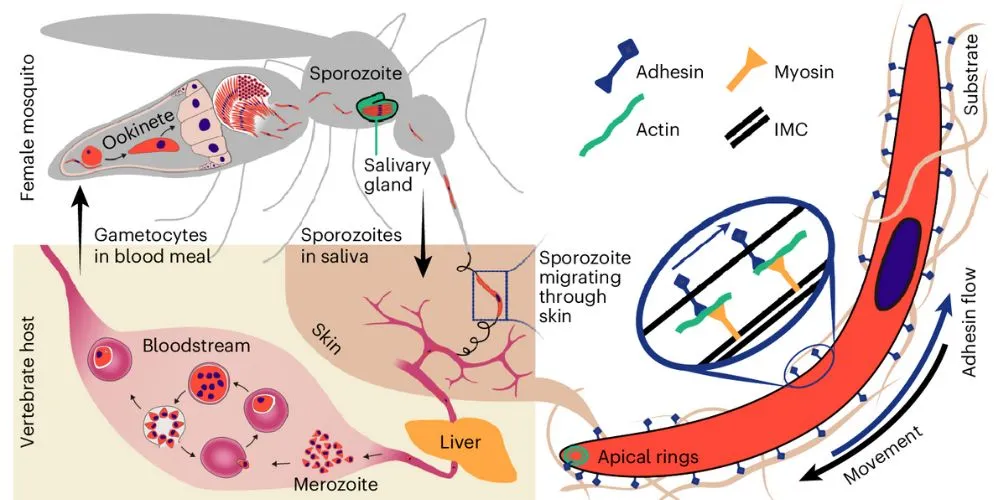

Malaria remains one of the deadliest diseases on Earth, and now scientists have uncovered a secret about how it moves through the human body. A team of physicists and researchers from Heidelberg University found that the malaria parasite almost always twists to the right as it travels. This discovery, published in the journal Nature Physics, explains how the germ navigates from a mosquito bite into a victim’s bloodstream.

The parasite, known as Plasmodium, enters the skin in the form of a tiny crescent moon. The research team used high-tech cameras and computer simulations to track its path. They observed that the organism moves in a helical, corkscrew pattern.

Just as a screw twists into wood, the parasite spirals to the right as it pushes through successive layers of tissue. This specific motion helps it wrap around blood vessels and grip slippery surfaces inside the body.

To see this happen, the scientists built a synthetic gel that acts like human flesh. They noticed a distinct difference in behavior across environments. When the parasites sat on a plain glass slide, they spun one way. However, when they crawled out of the 3D gel, they spun in the opposite direction.

This finding solves a long-standing mystery. For years, scientists struggled to infect liver cells in the lab. It turns out the parasites behave differently on flat glass than they do in actual tissue.

The team believes evolution designed this “right-handed” movement to help the pathogen switch between body parts—like moving from skin to blood to liver—without getting stuck. Computer models revealed that a slight lopsidedness at the front of the parasite creates the uneven force needed to turn right.

Now that researchers understand this steering mechanism, they can design better experiments. This will likely lead to more accurate testing for new drugs and vaccines to fight the disease.