In the quest for sustainable energy, humanity has looked to the sun, the wind, the tides, and the heat of the earth. We have built massive dams and covered deserts in silicon panels. However, one of the most promising and ubiquitous energy sources has been hiding right under our feet—or, more accurately, in the mud, sludge, and wastewater we try to hide away.

This is the world of Microbial Fuel Cells (MFCs). It is a technology that bridges microbiology and electrical engineering by harnessing bacteria’s natural metabolism to generate electricity. Imagine a world where wastewater treatment plants power themselves, where remote sensors on the ocean floor run indefinitely on sea mud, and where biodegradable batteries are grown rather than manufactured.

As the global energy crisis intensifies and the need for circular economies becomes paramount, MFCs represent a fascinating frontier. This guide delves into the science, applications, and future of generating electricity from bacteria.

The Science of Bio-Electricity

To understand how a Microbial Fuel Cell works, we must first understand how bacteria “breathe.” In aerobic respiration (as in humans), organisms consume nutrients (such as sugar) and use oxygen as the final electron acceptor to produce energy (ATP), releasing carbon dioxide and water as byproducts.

However, in oxygen-free environments (anaerobic conditions), certain bacteria must find alternative electron acceptors to accept electrons generated during their metabolic processes. In nature, they might use iron or sulfur. In an MFC, engineers trick these bacteria into dumping their electrons onto a solid electrode instead.

The Basic Architecture

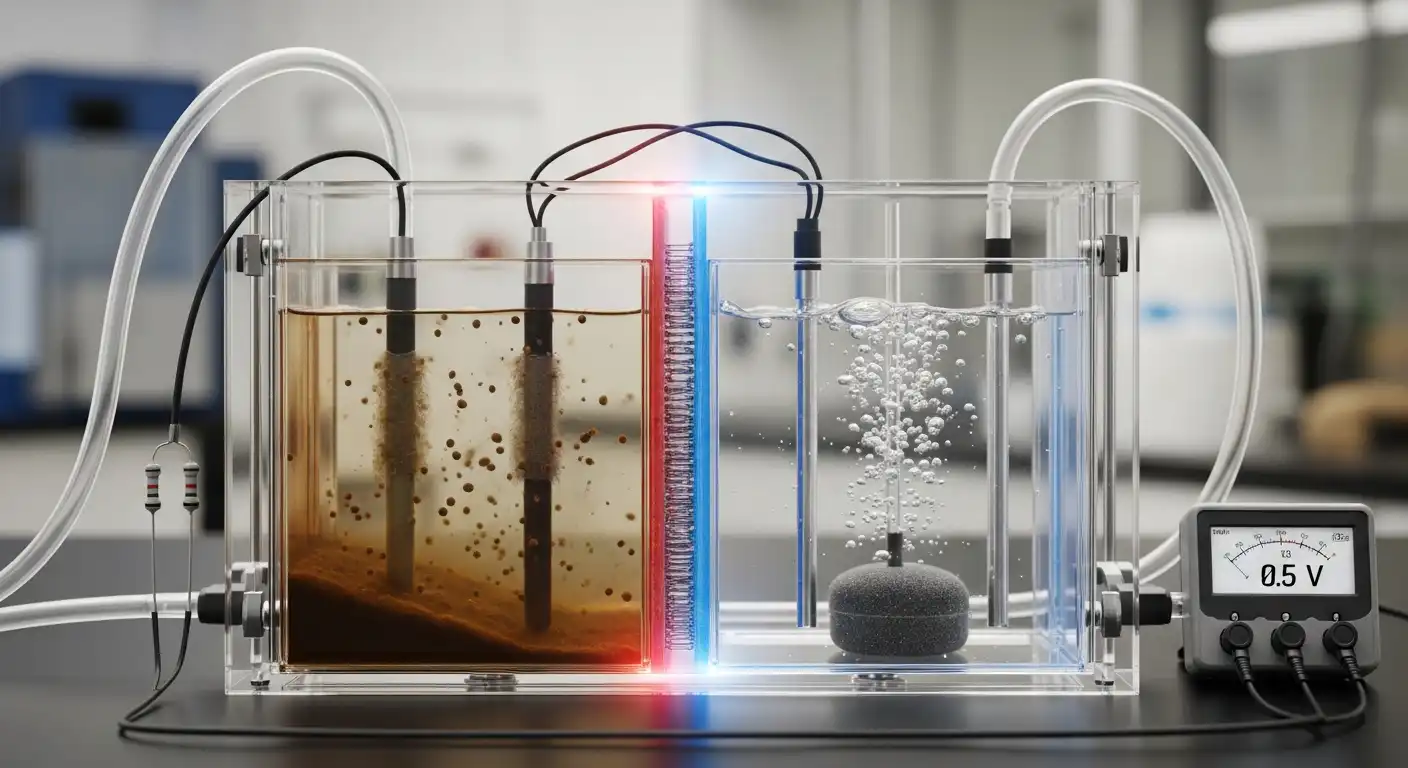

A standard MFC setup mimics the structure of a hydrogen fuel cell or a traditional battery, consisting of two chambers separated by a membrane.

- The Anode Chamber (Anaerobic): This is where the magic happens. Organic matter (fuel) and bacteria are placed here in an oxygen-free environment. The bacteria break down the organic matter (oxidation).

- The Cathode Chamber (Aerobic): This side contains an oxidant, usually oxygen from the air.

- The Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM): This separates the two chambers. It allows positively charged protons to pass through, but blocks electrons.

- The External Circuit: A wire connects the anode to the cathode.

The Electron Journey

The process flows as follows:

- The bacteria consume the organic fuel at the anode.

- This digestion releases electrons and protons.

- Because the bacteria are anaerobic “exoelectrogens” (more on them later), they transfer the electrons to the anode surface.

- The electrons travel through the external wire to the cathode, creating an electric current.

- Simultaneously, the protons pass through the PEM to the cathode.

- At the cathode, the electrons, protons, and oxygen combine to form pure water.

The result is a clean-energy generation system that processes organic waste and produces water as a byproduct.

Meet the Exoelectrogens: Nature’s Electricians

Not all bacteria are suited for life in an MFC. The stars of the show are a specific class of microbes known as exoelectrogens (or electrogenic bacteria). These organisms have evolved unique mechanisms to transfer electrons extracellularly—that is, outside of their own cell bodies.

Mechanisms of Electron Transfer

How does a microscopic organism connect to a piece of metal? Evolution has provided three ingenious solutions:

- Direct Electron Transfer (Nanowires): Some species, most notably Geobacter sulfurreducens, grow conductive protein filaments called pili, or “microbial nanowires.” These filaments physically touch the anode, creating a biological hardwire connection through which electrons flow.

- Direct Contact: Other bacteria form a dense biofilm on the anode surface. The outer membrane cytochromes (proteins) of the bacterial cell wall touch the electrode directly, facilitating the transfer.

- Mediated Transfer (Electron Shuttles): Some bacteria, like Shewanella oneidensis, can produce and secrete flavins or quinones. These molecules act as tiny ferries. They pick up electrons inside the cell, swim to the electrode, release them, and swim back to the cell to reload.

The Community Effect

In real-world applications, MFCs rarely use a single pure bacterial strain. Instead, they utilize a “consortium” of microbes found in wastewater or sediment. Some bacteria break down complex waste into simpler compounds, while the exoelectrogens consume those simple compounds to generate power. This symbiotic ecosystem makes the system robust and capable of degrading complex fuels such as sewage and agricultural runoff.

The Killer Application: Wastewater Treatment

While the idea of bacterial batteries is exciting, the current power output of MFCs is relatively low compared to solar or wind. You cannot yet run a city on bacteria. However, there is one industry where MFCs are poised to be a game-changer: Wastewater Treatment.

The Energy Problem in Water Treatment

Treating sewage is incredibly energy-intensive. In the United States alone, wastewater treatment accounts for roughly 3% of the nation’s total electricity load. The majority of this energy is used for “aeration”—pumping air into tanks so that aerobic bacteria can break down the waste.

The MFC Solution

MFCs turn this paradigm on its head.

- Energy Generation vs. Consumption: Instead of consuming energy to remove organic matter (measured as Biochemical Oxygen Demand, or BOD), MFCs utilize the organic matter as fuel. They treat the water while generating electricity.

- Sludge Reduction: Anaerobic processes in MFCs produce significantly less solid waste (sludge) than traditional aerobic methods. Handling and disposing of sludge is one of the most expensive parts of wastewater management.

If scaled effectively, MFC technology could transform wastewater treatment plants from energy consumers into energy-neutral or even energy-positive facilities.

Diverse Configurations and Innovations

The laboratory version of an MFC usually looks like a science fair experiment with beakers and wires. However, to make the technology commercially viable, engineers have developed a range of sophisticated configurations.

Single-Chamber MFCs

Dual-chamber designs are well-suited for research but bulky for use in applications. Single-chamber MFCs remove the cathode chamber. The anode is submerged in the wastewater, and the cathode is exposed directly to the air (air-cathode). This simplifies the design and reduces costs, though it requires careful management to prevent oxygen from leaking into the anode side.

Sediment Microbial Fuel Cells (SMFCs)

This is one of the simplest and most immediately useful designs. An anode is buried in the anaerobic mud of a river or ocean floor, and a cathode is floated in the oxygen-rich water above.

- Use Case: Powering remote environmental sensors. Meteorological buoys or acoustic sensors for tracking marine life can run indefinitely on the power generated by the bacteria in the mud, eliminating the need for expensive and dangerous battery replacement missions.

Plant-Microbial Fuel Cells (P-MFCs)

This integrates botany with bacteriology. Plants perform photosynthesis, producing sugars and excreting some of them through their roots into the soil (exudates). Bacteria in the soil break down these exudates to generate electricity.

- The Vision: Imagine a wetland or a rice paddy that not only grows food and filters water but also powers the village’s lights. This technology is currently being tested in “green roof” applications to power LED lighting.

Advantages of Microbial Fuel Cells

The appeal of MFCs extends beyond just electricity generation. They offer a suite of environmental benefits that make them a key technology for a circular economy.

Waste-to-Energy Efficiency

MFCs can use a wide range of fuels that are currently considered waste. Human sewage, agricultural manure, food scraps, and brewery wastewater can all be converted into electricity. This creates value from waste streams that would otherwise incur disposal costs.

Mild Operating Conditions

Unlike hydrogen fuel cells or combustion engines, MFCs operate at ambient temperature and neutral pH. They do not require high pressure, extreme heat, or dangerous chemicals to function. This makes them safe to install in residential or sensitive environmental areas.

Biosensing Capabilities

Because electricity generation is directly tied to bacterial metabolic activity, MFCs make excellent biosensors.

- Toxicity Monitoring: If a toxic chemical enters a water stream, the bacteria will get sick or die, causing an immediate drop in electrical current. This can trigger an alarm for water quality management systems instantly, faster than many chemical tests.

- BOD Monitoring: The amount of current produced is proportional to the amount of “food” (organic waste) in the water. This allows treatment plants to monitor pollution levels in incoming water in real time.

The Hurdles: Why Isn’t This Everywhere?

Given the benefits, why don’t compost heaps power our homes yet? Several significant technological and economic barriers remain.

The Power Density Challenge

The biggest limitation is power density. Currently, MFCs produce relatively low energy per unit volume. While they can power sensors or LEDs, they cannot compete with the power density of a lithium-ion battery or a combustion engine. The system’s internal resistance, the slow metabolism of bacteria relative to chemical reactions, and the difficulty of electron transfer all bottleneck the output.

The Cost of Materials

High-efficiency MFCs in labs often use expensive materials.

- Platinum: Often used as a catalyst on the cathode to speed up the reaction with oxygen.

- Nafion, the standard material for Proton Exchange Membranes, is costly.

- Titanium: Used for wiring to prevent corrosion.

For MFCs to be viable for municipal wastewater treatment, researchers are developing low-cost, durable alternatives, such as biocathodes (using bacteria to catalyze oxygen reduction) and ceramic membranes.

Scaling Up

In MFC technology, bigger is not always better. As the reactor size increases, the surface-area-to-volume ratio decreases, and the internal resistance increases. A 1-liter reactor works great; a 1,000-liter reactor often fails to produce 1,000 times the power. Engineers are solving this by “stacking” many small MFC modules rather than building a single giant tank, similar to how server farms stack hard drives.

Biofouling

Biological systems are messy. Over time, membranes can get clogged with bacterial growth, and electrodes can degrade. Maintaining a stable system over years of operation without intensive maintenance is a major engineering challenge.

The Future: Synthetic Biology and Nanotechnology

The path forward for Microbial Fuel Cells lies at the intersection of genetic engineering and material science.

Super-Charging Bacteria

Synthetic biology is allowing scientists to edit the genomes of exoelectrogens. Researchers are engineering strains of Geobacter or E. coli that produce more nanowires, carry more electron shuttles, or tolerate wider fluctuations in pH and temperature. We are effectively trying to breed “Olympic athlete” bacteria optimized for electricity generation.

Advanced Electrode Materials

Nanotechnology is revolutionizing the anode. By using graphene, carbon nanotubes, or modified biochar, scientists increase the surface area available for bacterial attachment. A rougher, more porous surface means more bacteria per square inch, which translates to higher current density.

Integration with Desalination

A fascinating derivative of MFC technology is the Microbial Desalination Cell (MDC). In this setup, the electric potential generated by the bacteria drives ions across membranes, thereby desalinating saltwater. This creates a holy grail system: a machine that takes in wastewater and saltwater, and outputs clean water and electricity.

Conclusion

Microbial Fuel Cells represent a paradigm shift in how we view waste. For centuries, we have viewed biological waste as a hazard to be neutralized. MFCs teach us that waste is merely misplaced energy.

While it is unlikely that MFCs will ever replace the grid or power high-performance vehicles, that is not their purpose. Their future lies in decentralized, sustainable utility. They will power the sensors that monitor our climate, make our water treatment plants self-sufficient, and provide light to remote, off-grid communities using nothing but the organic matter around them.

As we strive for a carbon-neutral future, the collaboration between human engineering and microbial metabolism offers a glimpse of a technology that works with nature, rather than against it. The revolution may not be televised, but the microbes in the mud might just power it.