When an oil tanker fractures against a reef or an offshore rig suffers a catastrophic blowout, the resulting black tide is one of the most visceral and devastating images of environmental destruction. The thick, toxic sludge coats seabirds, suffocates marine ecosystems, and destroys coastlines for decades. Traditional cleanup methods—skimmers, chemical dispersants, and controlled burns—are often expensive, logistically challenging, and can cause secondary environmental damage.

However, nature has its own solution, one that has been evolving for millions of years. Long before humans began drilling for fossil fuels, oil seeped naturally from the ocean floor. In response, the microbial world adapted. Today, scientists are harnessing these microscopic organisms in a process known as bioremediation—a technology that treats environmental contamination using life itself.

This comprehensive guide explores the science, application, and future of using microbes to clean up oil spills, detailing how these invisible heroes turn toxic disasters into harmless byproducts.

The Principles of Bioremediation

Bioremediation is the use of naturally occurring or deliberately introduced microorganisms to consume and degrade environmental pollutants, thereby cleaning a polluted site. While the concept sounds like science fiction, it is grounded in basic biology.

The Biological Imperative

At a molecular level, crude oil is a cocktail of hydrocarbons—organic compounds made of hydrogen and carbon. To us, it is either fuel or a pollutant. To certain bacteria, yeast, and fungi, it is food. Just as humans metabolize carbohydrates (sugar) for energy, these microbes metabolize hydrocarbons.

The goal of bioremediation is to accelerate this natural process of feeding. When successful, the microbes digest the complex, toxic hydrocarbon chains and convert them into harmless byproducts: primarily water (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), and biomass (more microbes). This process is known as mineralization.

The “Pac-Man” Effect

Imagine the oil spill as a buffet table and the microbes as hungry diners. In a pristine environment, these “diners” might be present in small numbers, but they lack the side dishes—nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus—necessary to sustain a feasting frenzy. Bioremediation strategies often focus on supplying these missing nutrients to boost the microbial population, allowing them to swarm the oil like Pac-Man eating dots.

The Microscopic Workforce: Hydrocarbonoclastic Bacteria

Not all bacteria can eat oil. The specific group of organisms capable of degrading hydrocarbons is known as Hydrocarbonoclastic bacteria (HCB). These organisms have evolved specialized enzymes that allow them to shear open the stubborn carbon bonds found in oil.

Alcanivorax borkumensis: The Star Player

Perhaps the most famous of these organisms is Alcanivorax borkumensis. In unpolluted waters, this rod-shaped bacterium is rare, found in negligible numbers. However, following an oil spill, its population explodes. Studies have shown that Alcanivorax can make up to 90% of the microbial community in oil-contaminated waters shortly after a spill.

Its superpower lies in its ability to produce biosurfactants. Oil and water do not mix; the oil floats on top, making it hard for bacteria living in the water to reach it. Biosurfactants are detergent-like biological molecules that reduce the surface tension between oil and water, thereby emulsifying the oil into small droplets. This increases the surface area, thereby making the oil more accessible to the bacteria for digestion.

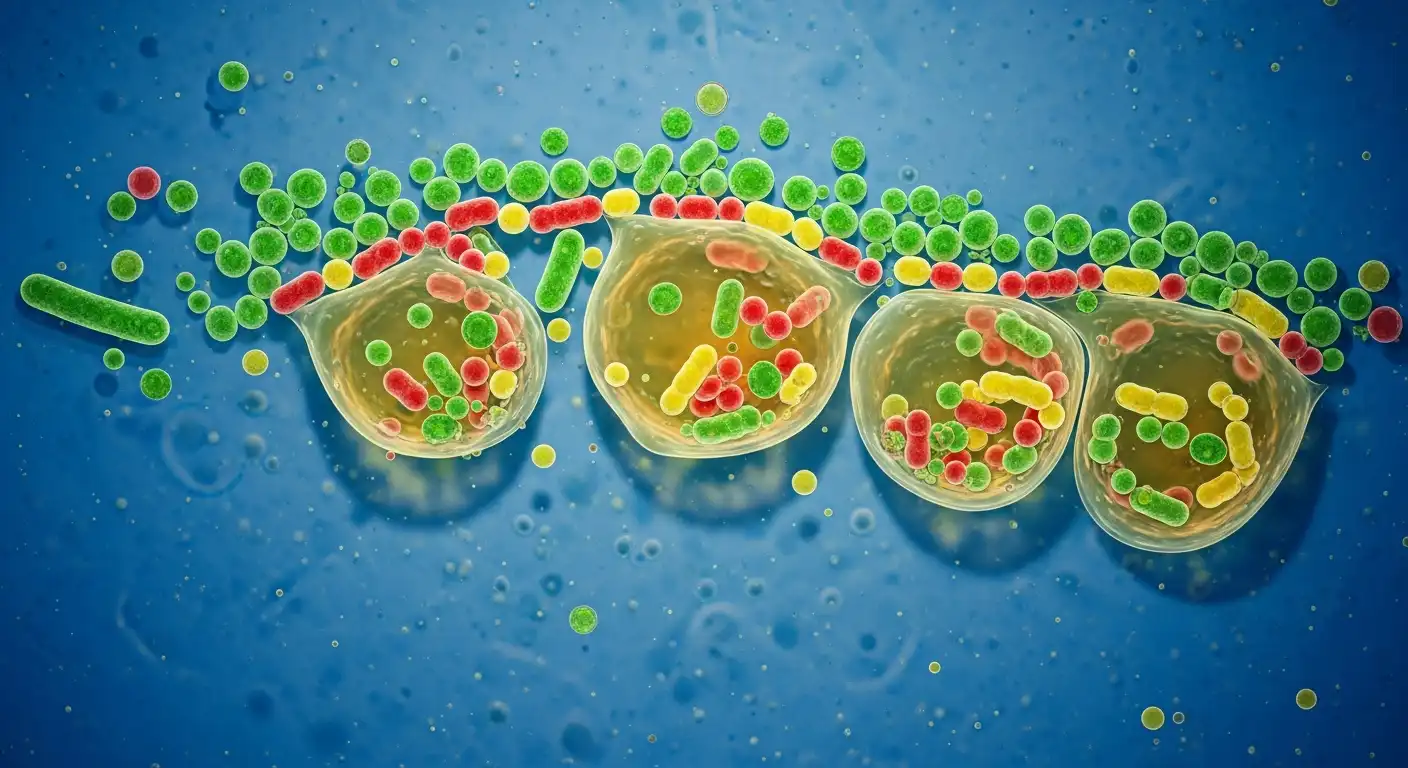

The Microbial Consortium

While Alcanivorax is a heavy lifter, it cannot do the job alone. Crude oil is complex, containing thousands of different compounds, including alkanes, aromatics, and resins. A single species usually cannot degrade all of them. Therefore, effective bioremediation relies on a microbial consortium—a team of different species working together.

- Pseudomonas: Known for its versatility, it can degrade a wide range of hydrocarbons.

- Cycloclasticus: Specializes in breaking down aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are among the most toxic and carcinogenic components of oil.

- Thalassolituus and Oleispira: Other key players that often appear in different temperatures and depths.

Strategies of Bioremediation

Scientists employ three primary strategies to deploy these microbes against oil spills. The choice of method depends on the location (land vs. sea), the type of oil, and the environmental conditions.

Biostimulation: Feeding the Natives

Biostimulation is the most common and often the most effective method used in open environments. It operates on the premise that oil-eating bacteria are already present in the ocean (indigenous capability) but are limited by nutrient availability.

Crude oil is rich in carbon but poor in nitrogen and phosphorus. Without these elements, bacteria cannot build proteins or DNA, limiting their growth. Biostimulation involves adding these fertilizers to the contaminated area.

The Oleophilic Fertilizer Breakthrough:

You cannot simply discharge garden fertilizer into the ocean; it will wash away or cause separate problems, such as algal blooms. Scientists have developed oleophilic (oil-loving) fertilizers. These adhere to the oil slick, ensuring that nutrients are delivered directly to the microbes feeding on the oil rather than dissolving into the surrounding water.

Bioaugmentation: Bringing in Reinforcements

Sometimes, the local microbial population is insufficient. This might happen in a freshly contaminated site with no history of oil exposure, or in extreme environments. Bioaugmentation involves introducing specific, laboratory-grown bacterial strains (allochthonous capability) known to be efficient oil degraders.

While this sounds ideal, it has a mixed success rate. Lab-grown bacteria often struggle to compete with native species that are better adapted to the local temperature, salinity, and predators. It is the ecological equivalent of dropping a house cat into the jungle; they are often outcompeted before they can do their job. However, modern approaches use “acclimatized” strains isolated from similar environments to improve survival rates.

Intrinsic Bioremediation: Natural Attenuation

In some sensitive ecosystems, such as salt marshes or deep mangrove forests, human intervention (heavy machinery or chemical spraying) causes more damage than the oil itself. In these cases, scientists may opt for Monitored Natural Attenuation. This means leaving the cleanup to natural processes while closely monitoring progress to ensure that the oil is degrading rather than migrating. It is a “no harm” approach that relies entirely on the unassisted background rate of microbial degradation.

Historic Case Studies: From Exxon Valdez to Deepwater Horizon

The viability of bioremediation is not theoretical; it has been battle-tested in some of the worst environmental disasters in history.

The Exxon Valdez (1989)

When the Exxon Valdez tanker ran aground in Prince William Sound, Alaska, spilling 11 million gallons of crude oil, it coated thousands of miles of pristine coastline. Physical cleaning (high-pressure hot water) proved damaging to the shoreline ecosystem.

The EPA initiated the largest biostimulation project in history. They applied nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers to the oil-coated rocks. The results were dramatic: treated areas exhibited oil degradation rates two to five times faster than untreated areas. Within weeks, rocks blackened with sludge began to show clear spots where the bacteria had eaten the oil away. This disaster demonstrated that biostimulation operates at a large scale.

Deepwater Horizon (2010)

The BP Deepwater Horizon blowout was a different beast. It released 134 million gallons of oil, much of it trapped in a deep-sea plume at a depth of 1,500 meters. Critics feared the deep ocean—cold, dark, and under immense pressure—would halt microbial activity.

Surprisingly, researchers discovered a massive bloom of cold-loving (psychrophilic) bacteria in the deep plume. Species like Oceanospirillales were feasting on the natural gas and propane dissolved in the water, while Colwellia and Cycloclasticus attacked the oil. The widespread use of chemical dispersants (Corexit) broke the oil into small droplets, which, while controversial for their own toxicity, effectively created a buffet for deep-sea microbes. It is estimated that microbes consumed a significant portion of the dispersed oil before it could even reach the surface.

The Advantages of Microbial Cleanup

Why choose bioremediation over traditional mechanical or chemical methods?

- Environmental Safety: It is a “green” technology. Unlike burning (which creates air pollution) or detergents (which can be toxic to fish), the byproducts of bioremediation are non-toxic. It creates a natural cycle of carbon recycling.

- Cost-Effectiveness: Deploying microbes and nutrients is significantly cheaper than hiring thousands of workers to scrub rocks or operating fleets of skimmer ships. It requires less equipment and energy.

- Accessibility: Microbes can reach places machines cannot. They can seep into rock pores, penetrate deep into sandy beaches, and function within the intricate root systems of wetlands, where mechanical removal is impossible.

- Permanence: Mechanical skimming removes most of the oil but leaves a residue. Bioremediation targets the molecular structure of the oil, permanently eliminating the pollutant rather than just moving it to a landfill.

Limitations and Environmental Challenges

Despite its promise, bioremediation is not a magic wand. It is a biological process governed by natural laws, and several factors can limit its effectiveness.

The Oxygen Bottleneck

Hydrocarbon degradation is an aerobic process—it requires oxygen. In the open ocean, this is rarely an issue. However, if oil sinks into sediments or marsh mud, the environment becomes anaerobic (oxygen-free). Anaerobic biodegradation occurs but is markedly slow—taking decades rather than months. Oxygenating these sediments without destroying the habitat is a major engineering challenge.

Temperature Sensitivity

Metabolism is ruled by thermodynamics. In warm tropical waters, bacteria work fast. In the freezing waters of the Arctic or Antarctic, metabolic rates plummet. As oil exploration moves into polar regions, the effectiveness of standard bioremediation techniques is called into question. Research is currently focused on identifying “psychrophiles”—cold-loving bacteria—that can function efficiently at near-freezing temperatures.

Toxicity Thresholds

While these bacteria eat oil, they are not immune to toxicity. High concentrations of heavy metals, often found in crude oil, or extremely high concentrations of the oil itself, can kill the microbial population. There is a “Goldilocks” zone: enough oil to sustain the population but not so much that it suffocates it.

The “Asphaltene” Problem

Microbes are adept at consuming the “light” components of crude oil (alkanes and simple aromatics). They are terrible at eating the heavy, tar-like components known as asphaltenes and resins. These heavy compounds effectively form the “road tar” that remains on beaches for years. While microbes can reduce the volume of a spill, they often leave behind this stubborn, heavy residue.

The Future: Genetic Engineering and Synthetic Biology

The frontier of bioremediation lies in the laboratory. While natural evolution is powerful, it is slow. Scientists are now looking to Genetically Engineered Microorganisms (GEMs) to build the ultimate oil-eaters.

Super-Bugs

Using CRISPR and other gene-editing tools, scientists can splice genes from different bacteria together. Imagine a bacterium that survives in freezing temperatures (gene from Arctic bacteria), produces massive amounts of biosurfactants (gene from Bacillus), and has the enzyme pathways to digest heavy resins (gene from Pseudomonas).

The “Suicide Switch”

The release of GEMs into the wild is highly controversial due to the risk of ecological disruption. What if the super-bug outcompetes natural algae? To counter this, scientists are engineering “suicide switches.” These genetic codes program the bacteria to die once the oil source is depleted, thereby preventing them from becoming invasive.

Mycoremediation: The Fungal Frontier

Bacteria aren’t the only players. Fungi, specifically white-rot fungi, produce powerful extracellular enzymes designed to break down lignin in wood. Since lignin shares a similar chemical structure with complex hydrocarbons, these fungi are highly effective at degrading the heavy, tar-like oils that bacteria leave behind. Future oil spill responses may employ a “one-two punch”: bacteria to consume light oil, followed by fungal spores to digest heavy residues.

Conclusion

Bioremediation represents a fundamental shift in how humanity manages its industrial footprint. It moves us away from the mechanical domination of nature and toward a partnership with it. By understanding and amplifying the metabolic capabilities of the microbial world, we can mitigate the damage of our reliance on fossil fuels.

It is not a cure-all. It cannot prevent the immediate physical trauma caused by a spill in marine life, nor can it eliminate all traces of sludge. However, as our understanding of genetics and microbial ecology deepens, bioremediation is becoming the standard for long-term environmental recovery. It is a modest reminder that the smallest organisms on Earth often hold the key to solving our most pressing problems. When we spill, nature cleans—we just need to help set the table.