Key Points

- Scientists have demonstrated that a massive nanoparticle composed of thousands of atoms can exist in a quantum superposition.

- The experiment is one of the most rigorous tests of quantum mechanics on a macroscopic scale ever performed.

- The “Schrödinger’s metal lump” was in two places at once, creating an interference pattern like a wave.

- The particle was larger than most proteins and comparable in size to a computer transistor.

Can a tiny lump of metal be in two places at the same time? According to a team of physicists at the University of Vienna, the answer is a definite yes. In a groundbreaking experiment, they have shown that even a relatively massive nanoparticle, made of thousands of atoms, still follows the bizarre rules of quantum mechanics.

In the quantum world, things can behave as both a particle and a wave. We’ve seen this with tiny things like electrons and atoms, but we don’t see it in our everyday lives. A baseball, for example, is always in one place at one time. This experiment pushes the boundary between the quantum and classical worlds further than ever before.

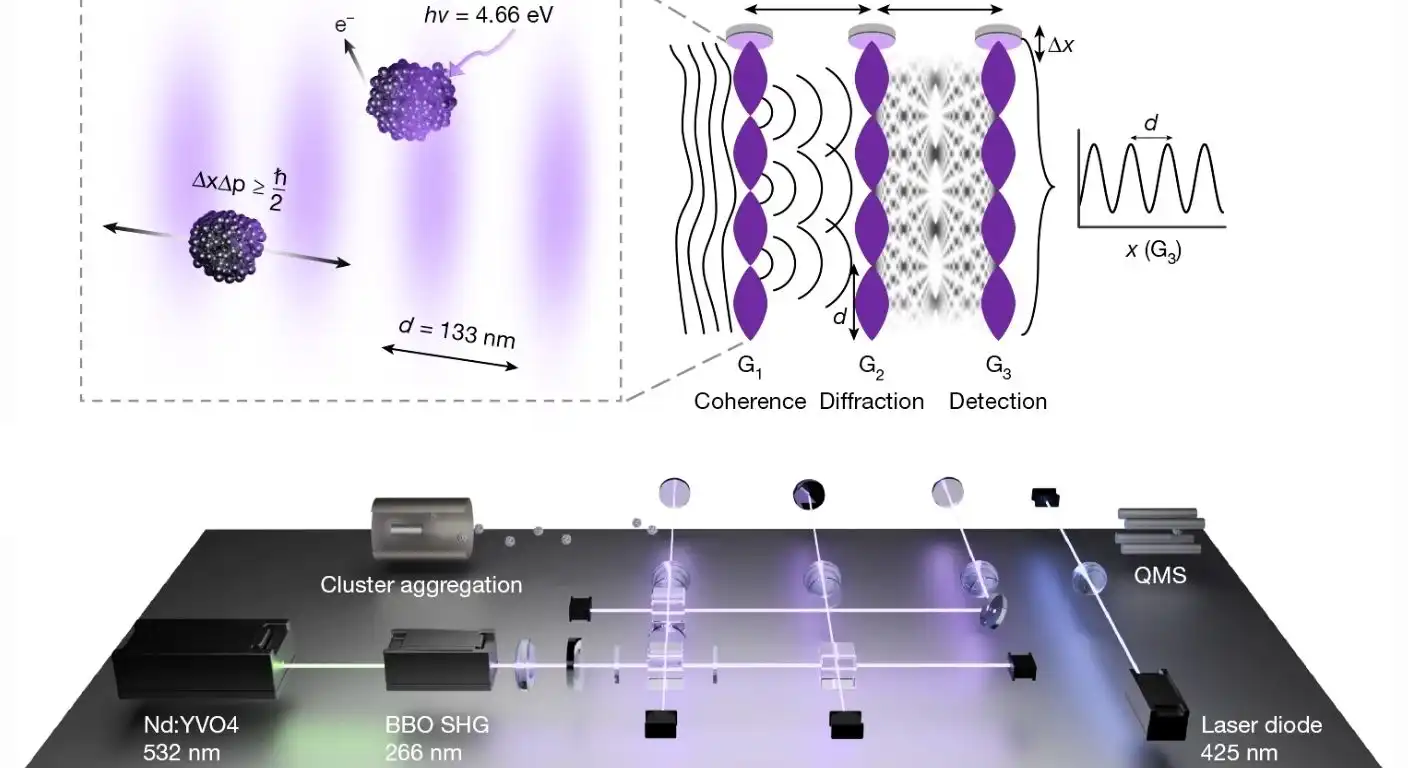

The scientists created a “Schrödinger’s metal lump” out of a cluster of up to 10,000 sodium atoms. This particle is larger than most proteins and comparable in size to the transistors on a modern computer chip. They then sent this particle through a series of laser beams that acted like a diffraction grating.

The result? The nanoparticle created an interference pattern, just like a wave of light would. This shows that, while in flight, the particle’s location was not fixed. It was in a “superposition” of all the possible paths it could have taken. As one of the lead authors put it, “every piece of metal is here and not here.”

This is one of the most rigorous tests of quantum mechanics on a macroscopic scale ever conducted. The “macroscopicity” of the experiment, a measure of how well it rules out any deviations from quantum theory, is an order of magnitude higher than any other experiment to date.

The experiment is a major step in helping us understand why the world we see every day seems so different from the strange and wonderful world of quantum physics.

Source: Nature (2026).