Key Points:

- Neonatal gut bacteria produce serotonin and down-regulate MAO-A to enhance serotonin. Rodentibacter is a key bacterium associated with serotonin production.

- Serotonin promotes immune tolerance by modulating T cell metabolism and promoting regulatory T cell differentiation.

- Three mechanisms contribute to enhanced serotonin availability in the neonatal gut: direct production, TPH1 activation, and MAO-A down-regulation.

- Further research is needed to understand the impact of early-life antibiotic treatment on neurotransmitter availability and serotonin’s effects on T cells.

A recent study published in Science Immunology illuminates the crucial role of neonatal gut bacteria in promoting immune tolerance through the production of serotonin. The findings highlight the intricate relationship between early-life gut microbiota, neurotransmitters, and immune responses.

The study underscores the significance of bacterial colonization in the neonatal gut for developing the immune system and intestinal maturation. It points out that children with certain health conditions, such as asthma and food allergies, often exhibit altered gut microbiotas and metabolomes, emphasizing the importance of understanding the neonatal metabolome’s influence on immune tolerance.

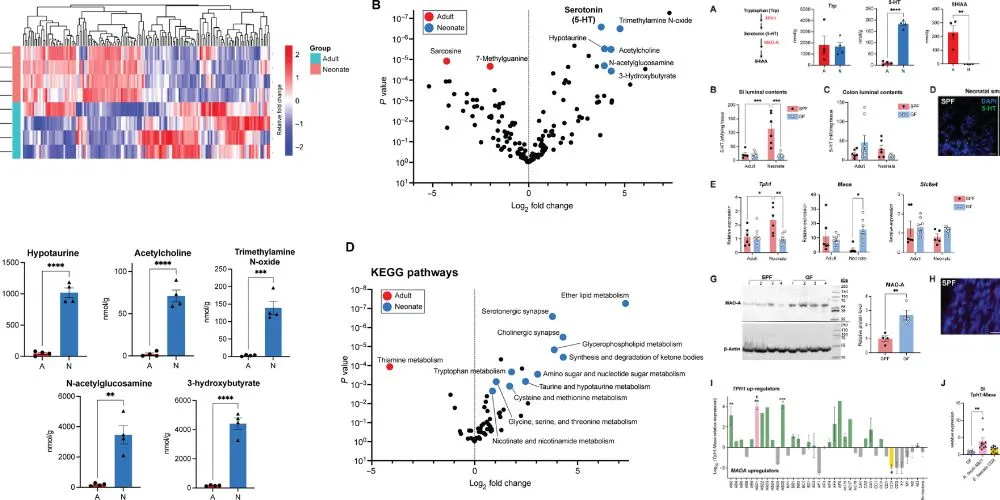

Researchers delved into the presence of neurotransmitters in the neonatal small intestine (SI) and conducted both in vitro and in vivo experiments to evaluate immune tolerance against gut commensal bacteria and oral antigens. Their investigations revealed that serotonin is pivotal in fostering immune tolerance during early life.

Interestingly, the study found that neonatal gut bacteria, rather than epithelial enterochromaffin cells (ECs), are the primary source of serotonin in the neonatal gut. Furthermore, gut microbes were observed to down-regulate monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) to limit serotonin breakdown, thereby enhancing its availability.

Experimental evidence demonstrated that serotonin administration to germ-free neonates, followed by oral antigen sensitization, facilitated long-term immune tolerance in adulthood. This effect was attributed to serotonin’s ability to modulate T cell metabolism and promote the differentiation of regulatory T cells, crucial for immune tolerance.

The study also identified Rodentibacter as a key neonatal gut bacterium associated with serotonin production. Notably, the composition of neonatal microbiota differed between the small intestine and colon, highlighting regional variations in microbial communities and their functional roles.

Moreover, the study elucidated three independent mechanisms through which neonatal gut bacteria enhance serotonin availability, including direct production, activation of tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1), and reduction of serotonin breakdown.

Looking ahead, the researchers advocate for further investigation into the contribution of SI microbiota to early-life immunity and the impact of early-life antibiotic treatment on neurotransmitter availability. Additionally, they emphasize the need to explore serotonin receptors or transporters that influence serotonin’s effects on T cells, paving the way for a deeper understanding of gut-brain-immune interactions.