On a global scale, the demand for human organs far outstrips the supply. In the United States alone, over 100,000 people are currently waiting for a life-saving organ transplant. Every day, 17 of those people die while waiting. The numbers are a stark reminder of the limits of modern medicine: we have the surgical skill to replace failing hearts, kidneys, and livers, but we lack the spare parts.

For decades, scientists have looked to the animal kingdom for a solution. This field is known as Xenotransplantation—the transplantation of living cells, tissues, or organs from one species to another. Specifically, researchers have focused on the pig (Sus scrofa) as the ideal donor for humans.

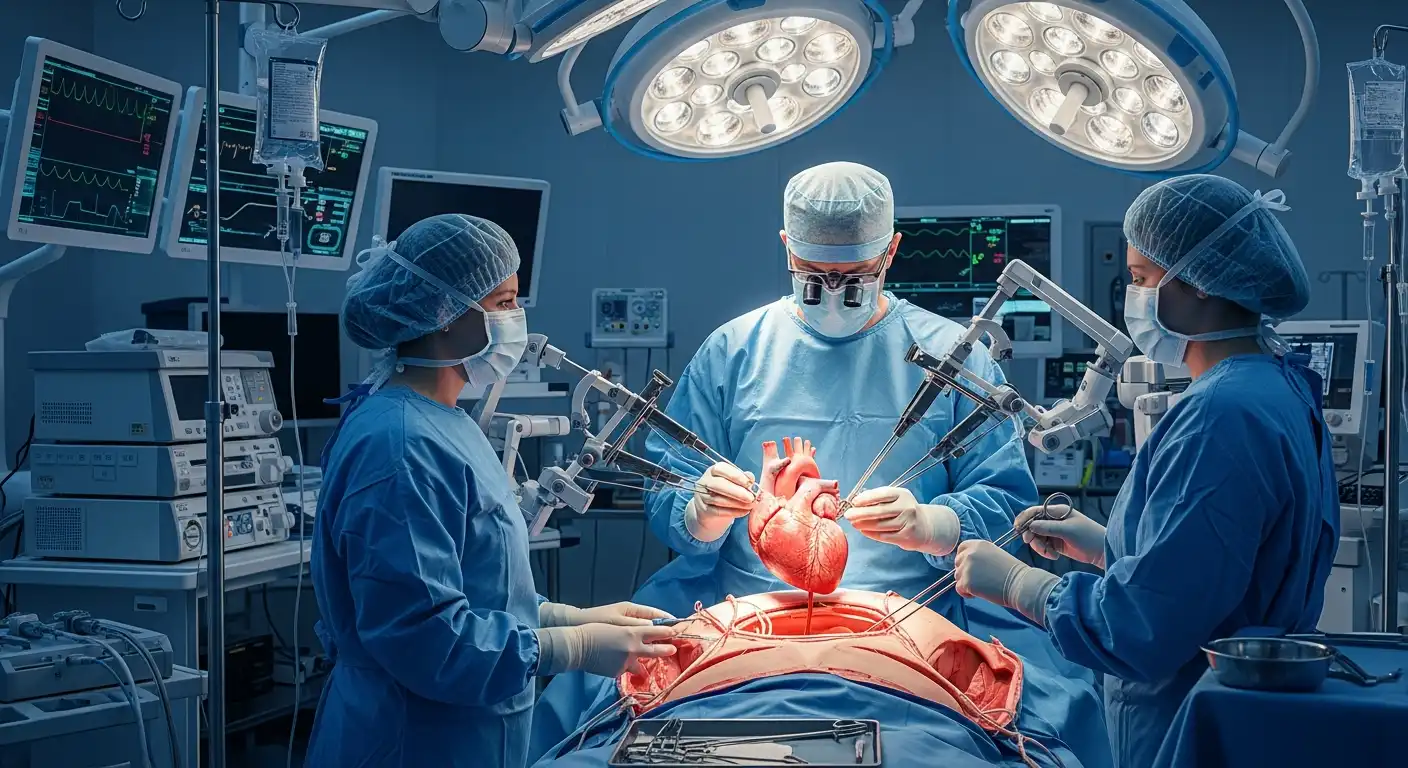

Recent breakthroughs in gene editing (CRISPR) have moved this from science fiction to reality. In 2022 and 2023, the world witnessed the first transplants of genetically modified pig hearts into human patients. While these experiments represent monumental scientific achievements, they have ignited a firestorm of ethical debate. Are we crossing a fundamental biological line? Is it right to breed animals solely as “spare parts”? And what are the risks of introducing new animal viruses into the human population?

This article examines the science, potential, and profound moral questions surrounding the future of pig-to-human transplants.

The Science: Why Pigs?

When people think of our closest biological relatives, they usually think of primates like chimpanzees or baboons. Indeed, early xenotransplantation attempts in the 1960s and 80s (such as the famous “Baby Fae” case) used baboon hearts. However, primates are problematic donors. They reproduce slowly, their organs are often too small for adult humans, and the ethical concerns regarding their high intelligence are significant.

Pigs, surprisingly, are the “Goldilocks” donor for humans.

- Anatomical Similarity: Pig organs are remarkably similar in size and physiology to those of humans. A pig heart pumps blood at a similar pressure and volume as a human heart.

- Availability: Pigs are already farmed by the billions for food. They reach adult size in six months and have large litters, making them readily available for scaling up organ production.

- Genetic Malleability: The pig genome is relatively easy to edit, which is the key to overcoming the biggest hurdle: rejection.

The Rejection Problem and CRISPR

The human immune system is a ruthless defender. If you put a standard pig heart into a human, the body would instantly recognize it as foreign. This triggers “Hyperacute Rejection,” where the organ turns black and dies within minutes. This happens because pig cells are coated in a sugar molecule called alpha-gal. Humans have natural antibodies that recognize alpha-gal.

Enter CRISPR-Cas9. This gene-editing technology allows scientists to go into the pig embryo and “knock out” the genes responsible for producing alpha-gal and other immunogenic sugars. Furthermore, they can insert human genes (transgenes) that produce proteins to “calm down” the human immune system and prevent blood clotting. The resulting pigs are essentially “humanized” at the cellular level, making their organs invisible to the recipient’s immune system.

The Ethical Landscape

While science is advancing rapidly, ethics are struggling to keep up. The debate is multifaceted, involving animal rights, patient safety, and societal definitions of humanity.

Animal Welfare and Rights

The most immediate ethical objection comes from animal rights advocates. Xenotransplantation requires breeding pigs specifically for organ harvesting. These animals are raised in sterile, medical-grade environments (biosecure facilities) to prevent disease, and they live completely removed from a natural environment.

- Instrumentalization: Critics argue that this reduces a sentient living being to nothing more than a biological container of spare parts. It is the ultimate form of instrumentalization—viewing the animal solely as a means to a human end.

- The Counter-Argument: Proponents argue that society already accepts the slaughter of over 1 billion pigs annually for food (bacon and ham). Killing a pig to save a human life (a heart transplant) is arguably a “higher” moral purpose than killing a pig for a sandwich. If we accept meat consumption, the argument goes, we must logically accept Xenotransplantation.

The Risk of Zoonosis (Xenozoonosis)

The most terrifying risk of Xenotransplantation is not to the individual patient, but to the human species. Animals carry viruses. Pigs, in particular, carry Porcine Endogenous Retroviruses (PERVs). These are viral DNA sequences embedded in the pig’s genome that have been passed down for millennia.

Although harmless to pigs, these viruses could potentially infect humans (zoonosis). Once in a human host, the virus could mutate and spread to nurses, family members, and the general public, potentially triggering a new pandemic.

- Mitigation: Scientists are using CRISPR to hunt down and deactivate all PERV sequences in the donor pig genome. While early tests show promise, the risk of an unknown pathogen “jumping species” remains a non-zero probability that keeps epidemiologists awake at night.

Patient Consent and Psychological Impact

The recipients of the first xenotransplants have been patients with no other options—terminally ill individuals ineligible for human donor lists. However, as the technology progresses to clinical trials, obtaining informed consent becomes more complex.

- Desperation: Can a dying patient truly give voluntary consent, or is the coercion of death too strong?

- Psychological Burden: How does living with a pig’s heart affect a person’s sense of self? There are documented cases of transplant recipients feeling “changed” by their human donor organs. The psychological impact of having an animal organ—often viewed as “unclean” in certain cultures and religions—is uncharted territory.

Religious and Cultural Concerns

For Jewish and Muslim patients, the pig is considered distinctively unclean (non-kosher/haram). While most religious scholars agree that strict dietary laws can be suspended to save a life (pikuach nefesh in Judaism), it still presents a significant cultural hurdle. Would a devout patient accept a pig valve or a kidney? Would their community accept them?

The Future: Bridge or Destination?

Is Xenotransplantation the final solution to the organ shortage, or just a bridge?

Currently, Xenotransplantation is often viewed as a “bridge to transplant.” A patient in acute heart failure might receive a pig heart to keep them alive for a few months until a human heart becomes available. However, the ultimate goal is for these organs to be “destination therapies”—permanent replacements that last for decades.

Alternatives on the Horizon

The ethical weight of Xenotransplantation is substantial, and it faces competition from technologies that may render it obsolete before it fully matures.

- 3D Bioprinting: Scientists are developing methods to print organs using patients’ own stem cells. This would eliminate rejection and ethical issues involving animals.

- Mechanical Organs: Artificial hearts (e.g., the Total Artificial Heart) and wearable dialysis machines are advancing. If a machine can do the job, we don’t need the pig.

However, these technologies are likely decades away from routine clinical use. The pig is here now.

Regulatory Hurdles and Oversight

In the United States, the FDA regulates xenotransplantation products. The recent surgeries (like the one on David Bennett in 2022) were performed under “Compassionate Use” authorizations—emergency permission granted when a patient faces certain death.

Moving from emergency cases to standard Clinical Trials requires rigorous proof that the zoonotic risk is managed. Regulators must balance the desperate need for organs against the public health risk of introducing a new virus. Early recipients of animal organs will likely be subject to lifetime monitoring—essentially living in a “surveillance state” where the government constantly tracks their health and contacts to prevent an outbreak.

Conclusion

Xenotransplantation forces us to do a brutal moral calculus. On one side of the scale is the suffering of hundreds of thousands of humans dying of organ failure. On the other side is the welfare of animals and the remote but catastrophic risk of a new pandemic.

There is no easy answer. But as the gene-editing scissors of CRISPR become sharper, the barrier between species is dissolving. We are entering an era where the definition of “human” biology is becoming fluid. Whether this is a triumph of human ingenuity or a hubristic step too far remains the defining bioethical question of our time.

For now, the pig stands at the center of modern medicine—not just as a source of food, but as the potential savior of the broken human heart.