Key Points:

- Osaka University team created pores approaching the size of atoms.

- The technique uses a miniature electrochemical reactor to open and close pathways.

- Scientists aim to mimic the ion channels found in human cell membranes.

- The process is controllable and can be repeated hundreds of times.

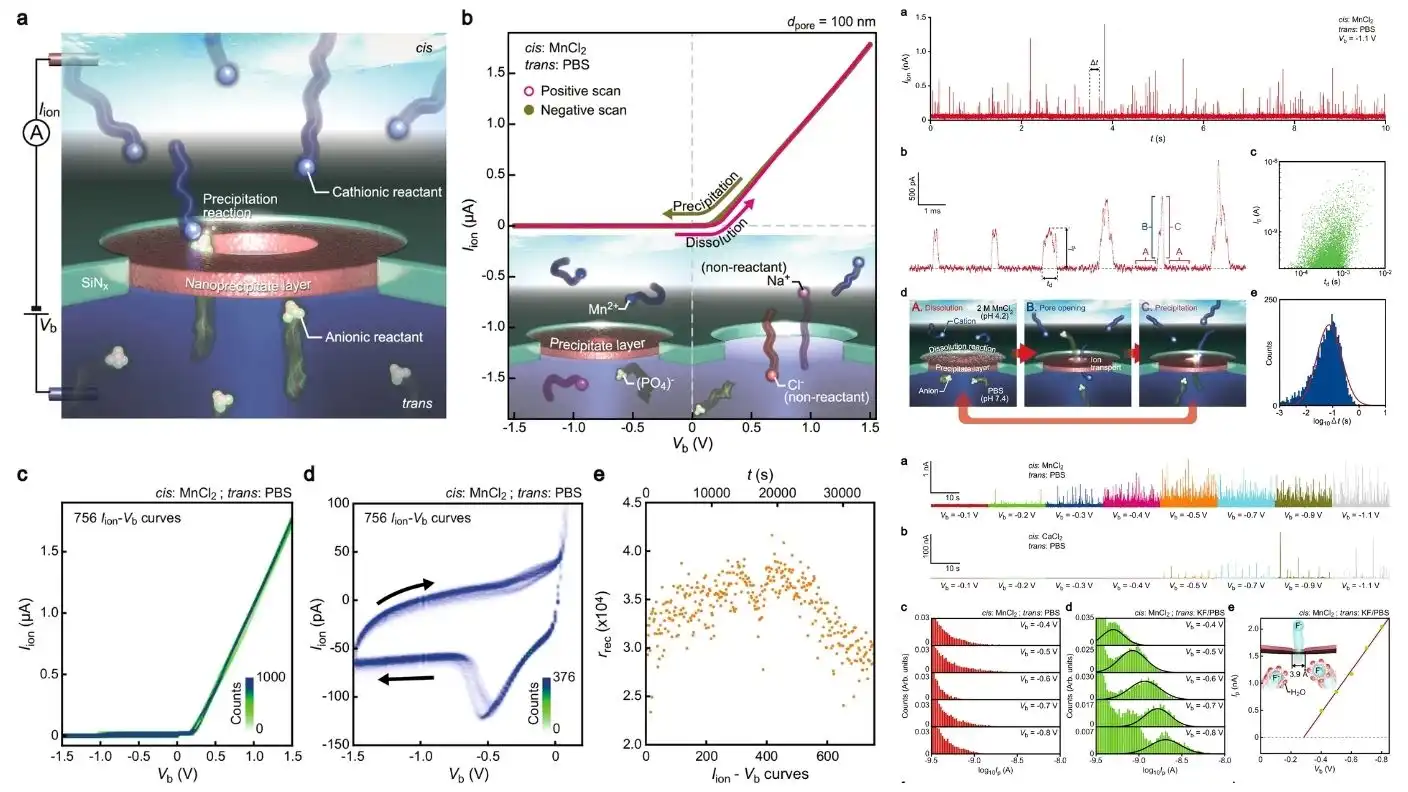

Researchers at Osaka University in Japan have found a way to create incredibly small holes, some just a few angstroms wide. This breakthrough, published in Nature Communications, solves a major challenge in nanotechnology. It allows scientists to build structures that mimic the tiny ion channels found in the human body.

These microscopic passageways are vital for life. Ions flow in and out of our cells through these channels, creating the electrical signals that power our nerves and muscles. The channels themselves are made of proteins that can open and close. Replicating this process in a lab has been extremely difficult because it requires working with materials the size of single atoms.

To solve this, the Japanese team turned a nanoscale pore into a tiny chemical reactor. They started by creating a small hole in a silicon membrane. Then, they applied a negative voltage, which caused a solid substance to form and completely block the opening. By reversing the voltage to positive, they dissolved the blockage, reopening tiny conductive pathways within the larger pore.

The team could repeat this process hundreds of times, proving that the method is both robust and controllable. “We were able to repeat this opening and closing process hundreds of times over several hours,” explained lead author Makusu Tsutsui.

By measuring the electrical current flowing through the membrane, the scientists observed spikes similar to those seen in biological systems. They believe these spikes show that their method creates many subnanometer pores within the single larger pore. Senior author Tomoji Kawai noted that they could change the size of these tiny openings by adjusting the pH of the chemical solutions. This allowed them to selectively filter different types of ions, just like a real cell.

This precise control has huge potential for future technology. The team believes this system could improve single-molecule sensing, a process used to sequence DNA. It could also lead to “neuromorphic” computers that use electrical spikes to act like biological neurons, essentially creating a computer chip that thinks like a brain.

Source: Nature Communications (2026).