When we think of the great frontiers of exploration, we often look to the stars. Yet, right here on Earth, there is a realm as mysterious and hostile as space: the deep ocean. It is a world of crushing pressure, eternal darkness, and extreme temperatures. For decades, it was assumed to be a barren wasteland. We were wrong.

The deep sea is teeming with life. And not just any life—extremophiles. These organisms have evolved unique biological mechanisms to survive where life should not exist. Within their genetic code lies the potential for the next generation of antibiotics, cancer treatments, and industrial enzymes.

This is the world of Deep Sea Bioprospecting. It is the hunt for genetic gold in the abyss. As antibiotic resistance threatens global health and the demand for sustainable industrial chemicals rises, pharmaceutical companies and governments are racing to the bottom of the ocean.

This comprehensive guide explores the science, the potential, and the ethical dilemmas of mining the deep sea for medicine.

Why the Deep Sea? The Extremophile Advantage

To find unique chemicals, you need unique organisms. Terrestrial biology (plants and animals on land) has been thoroughly scavenged. We have screened the rainforests. The deep sea offers a chemical diversity found nowhere else.

Adapting to Pressure and Darkness

Organisms living at 2,000 meters depth face pressure 200 times greater than at the surface. They live in near-freezing water or, near hydrothermal vents, in water hot enough to melt lead (400°C). To survive, they produce “secondary metabolites”—complex chemical compounds used for defense, communication, and structural integrity.

These compounds are often highly potent. Because the ocean dilutes chemicals rapidly, marine organisms must produce toxins and signals that are effective even at low concentrations. This high potency makes them ideal candidates for pharmaceutical drugs.

The Hydrothermal Vent Ecosystem

Hydrothermal vents are the hotspots of bioprospecting. These “black smokers” spew mineral-rich, superheated water. Bacteria here thrive on chemosynthesis (eating chemicals) rather than photosynthesis.

- Hyperthermophiles: Bacteria that love heat. Their enzymes are heat-stable, making them incredibly valuable for industrial processes that require high temperatures (like refining biofuels or PCR DNA testing).

Success Stories: Drugs from the Deep

Deep-sea bioprospecting is not just theoretical; it has already saved lives.

Yondelis (Trabectedin)

Derived from the sea squirt Ecteinascidia turbinata, this was the first marine-derived anticancer drug approved in the EU. It is used to treat soft tissue sarcoma. While the sea squirt isn’t strictly “deep sea” (it lives in mangroves and reefs), it proved the concept that marine invertebrates are chemical factories.

Prialt (Ziconotide)

This painkiller is derived from the venom of the Cone Snail. It is 1,000 times more potent than morphine but is non-addictive. It works by blocking calcium channels in the spinal cord, stopping pain signals.

Halaven (Eribulin)

Based on a molecule found in the marine sponge Halichondria okadai, this drug is used to treat metastatic breast cancer. It works by preventing cancer cells from dividing.

The PCR Revolution

While not a drug, the most famous marine discovery is the enzyme Taq Polymerase. Discovered in bacteria in hot springs (and similar versions found in deep-sea vents), this heat-resistant enzyme made the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) possible. Without it, we wouldn’t have modern DNA testing, forensics, or COVID-19 tests.

The Technology: How Do We Harvest the Abyss?

Bioprospecting is difficult. You cannot scuba dive to the bottom of the Mariana Trench. It requires technology usually reserved for oil exploration or the military.

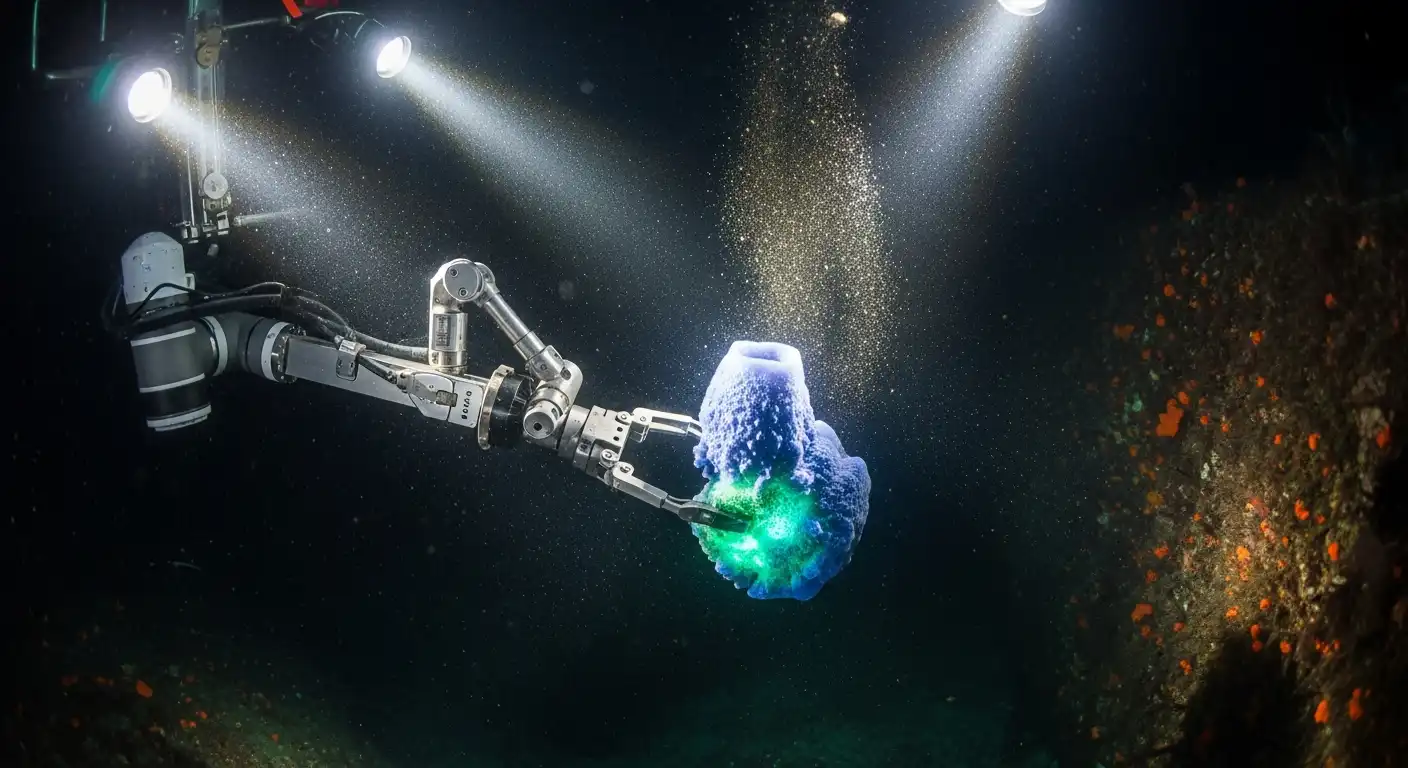

ROVs and Submersibles

Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) are the workhorses. Tethered to a mothership, these robots use robotic arms to gently pluck sponges, scoop sediment, or suction up jellyfish. They are equipped with high-definition cameras and sensors to record the precise environmental conditions (temperature, depth) where the sample was found.

Metagenomics: Mining DNA, Not Animals

In the early days, scientists needed pounds of a sponge to extract a milligram of a drug. This was ecologically devastating.

Today, we use Metagenomics. Scientists scoop up a cup of mud or water. They sequence all the DNA in that sample. By analyzing the genetic code on a computer, they can identify gene clusters that look like they produce interesting chemicals. They then synthesize these chemicals in a lab using bacteria (like E. coli) as factories. This means we can discover drugs without over-harvesting the deep-sea ecosystem.

The Legal and Ethical Battlefield

Who owns the bottom of the ocean? This is the most contentious question in bioprospecting.

The “Common Heritage of Mankind”

Under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the mineral resources of the deep seabed in international waters are the “Common Heritage of Mankind.” Profits from mining manganese nodules must be shared with developing nations.

However, the law is fuzzy regarding Marine Genetic Resources (MGRs).

- Developed Nations (Global North): Argue for “Freedom of the Seas.” Whoever has the technology to get the genes keeps the patents and the profits.

- Developing Nations (Global South): Argue that MGRs should also be “Common Heritage.” They fear “biopiracy,” where wealthy nations plunder the ocean’s genetic wealth and sell it back to the world as expensive medicine.

The BBNJ Treaty

In 2023, the UN finally agreed on the “High Seas Treaty” (BBNJ – Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction). This landmark agreement attempts to set rules for sharing the benefits of marine genetic resources, aiming to ensure equitable access and conservation.

Conservation Concerns

Bioprospecting is often seen as the “cleaner” cousin of deep-sea mining (mining for metals). However, it carries risks.

- Physical Damage: ROVs can damage fragile coral structures that took centuries to grow.

- Over-harvesting: If a sponge produces a miracle cure and we cannot synthesize it in a lab, there is immense economic pressure to trawl the ocean floor to get it, potentially driving species to extinction before they are even fully understood.

The Future: The Blue Pharmacy

The ocean represents the largest habitat on Earth, yet more than 80% of it remains unmapped and unexplored. We have likely discovered less than 1% of the bioactive compounds hidden in the deep.

As AI improves our ability to predict drug structures from genomic data, and as robotics allows us to reach deeper into the trenches, the “Blue Economy” will explode. The cure for the next pandemic, the solution to antibiotic resistance, or the enzyme that degrades plastic waste likely lies waiting in the dark, cold crushing depths. The race is on to find it—hopefully, before we destroy the ecosystem that created it.