Key Points

- Researchers found that drug effectiveness depends on the speed of receptor activation.

- Receptors become trapped in “kinetic traps” or intermediate conformations during the process.

- Stronger drugs push through these traps quickly, while weaker ones get stuck.

- The team used “molecular movies” to watch these proteins move in real time.

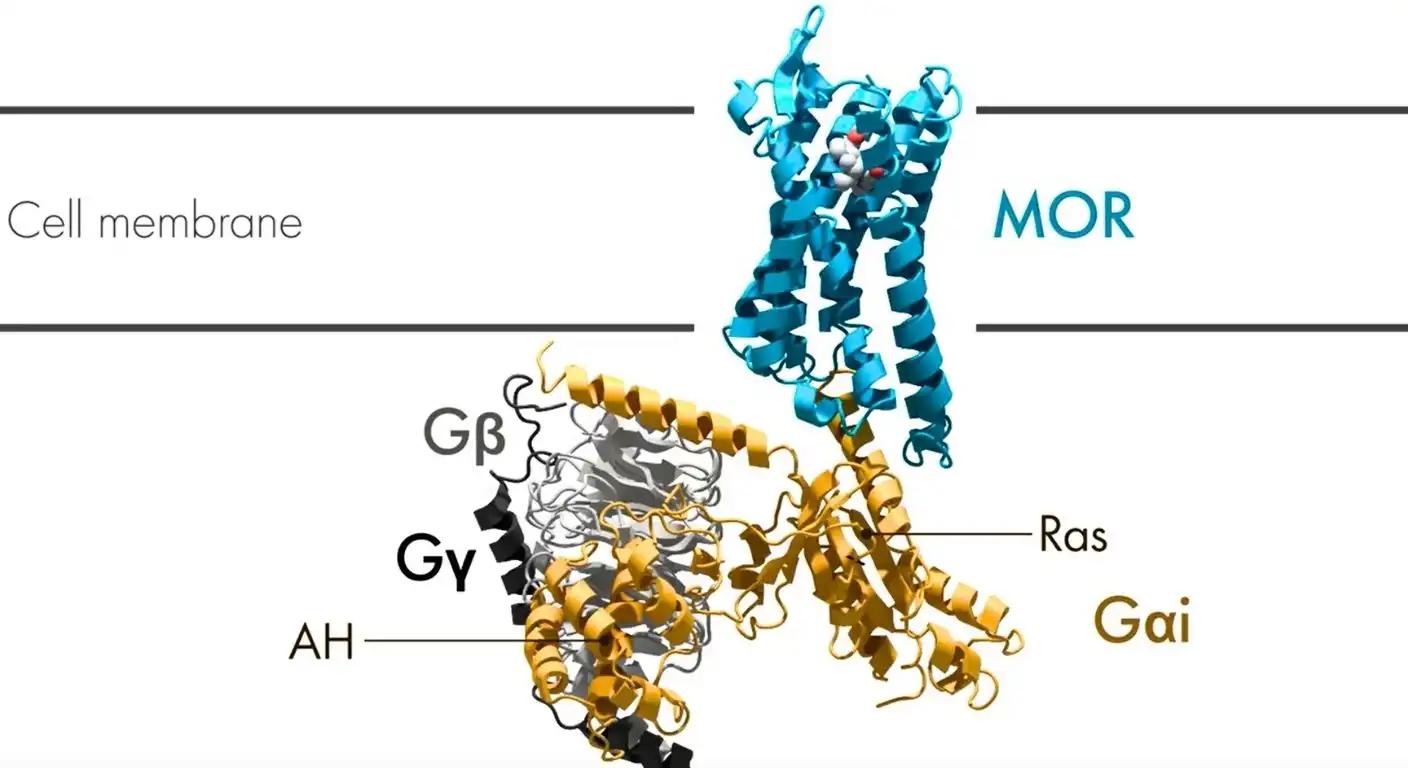

Scientists at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital just discovered why some drugs work effectively while others barely make a dent, even when they target the same spot in the body. They studied a group of proteins called G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs). These proteins act like tiny sensors on the surface of your cells. When a drug or a natural chemical lands on them, they change their shape to send a message inside the cell, telling it how to react.

Even though many different medicines target the same sensor, they don’t all produce the same result. For example, some painkillers provide massive relief, while others are much weaker. To date, researchers have not fully understood why this occurred.

Using advanced microscopes to capture “molecular movies,” the team found that the secret lies in speed and “sticky” intermediate steps.

The researchers focused on the mu-opioid receptor, which is the main target for painkillers like morphine and codeine. They observed that, as the receptor changes shape to transmit a signal, it must pass through several intermediate stages. They refer to these stages as “kinetic traps.”

Imagine a ball rolling down a hill toward a goal. A strong drug—which scientists call a “super agonist”—gives the ball enough energy to roll right over small bumps and divots in the grass without stopping. It reaches the bottom almost instantly. A weaker drug doesn’t provide as much of a “push.” The ball becomes caught in a small hole or divot for a long time before it finally climbs out and continues.

While both drugs eventually send the same message, the weaker one takes much longer to get through the process. This delay accounts for the drug’s reduced effect on the body.

This discovery is a breakthrough for medicine. About one-third of all FDA-approved medicines target these types of sensors. By understanding how to control the speed of these molecular movements, scientists can design better treatments. This could lead to new painkillers that work well but are much safer, helping to fight the opioid crisis and improve many other types of medicine.

Source: Nature (2025).