In July 1996, a sheep named Dolly was born in Scotland, forever changing the landscape of biology. She was not born from the union of a sperm and an egg, but rather from the DNA of an adult mammary gland cell. Dolly was the first mammal successfully cloned from an adult somatic cell, proving that the specialized DNA of a mature cell could be “rebooted” to create an entirely new organism.

The technology behind Dolly—and the thousands of cloned animals that have followed—is known as Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (SCNT). While pop culture often portrays cloning as a push-button sci-fi magic trick, the reality is a complex, delicate, and often inefficient biological procedure that sits at the cutting edge of embryology and genetics.

This comprehensive guide delves into the intricacies of SCNT, exploring the step-by-step biological mechanism, its applications in medicine and agriculture, the persistent scientific hurdles, and the profound ethical questions it raises.

Understanding the Terminology: What is SCNT?

To understand the process, we must first dissect the name itself. It provides the roadmap for the entire procedure:

- Somatic Cell: In biology, cells are classified into two categories: germ cells (sperm and eggs) and somatic cells (all other cells). Your skin, liver, muscle, and brain cells are all somatic. They contain the complete genetic code (diploid DNA) but are specialized to perform specific functions.

- Nucleus: The command center of the cell that houses the chromosomes (DNA).

- Transfer: The act of moving the nucleus from one cell to another.

Therefore, SCNT is the process of removing the nucleus from a body cell and transferring it into an egg cell whose own genetic material has been removed.

The Biological Pre-Requisites

Before SCNT can be performed, scientists need two distinct cellular components:

The Donor Cell (The Blueprint)

This is the somatic cell that provides the clone’s genetic material. In theory, almost any cell from the body could work, but fibroblasts (skin cells) are commonly used because they are easy to culture in a lab. Crucially, this cell must be “quiescent,” meaning it is induced to stop dividing. This state facilitates the synchronization of donor DNA with the recipient egg.

The Recipient Cell (The Factory)

This is an oocyte (an unfertilized egg cell). The egg cell is unique in biology because it contains the cytoplasmic machinery required to reprogram DNA. It is the only cell capable of turning a specialized nucleus back into a totipotent state—a state where it can become any type of cell in the body.

The Step-by-Step Process of SCNT

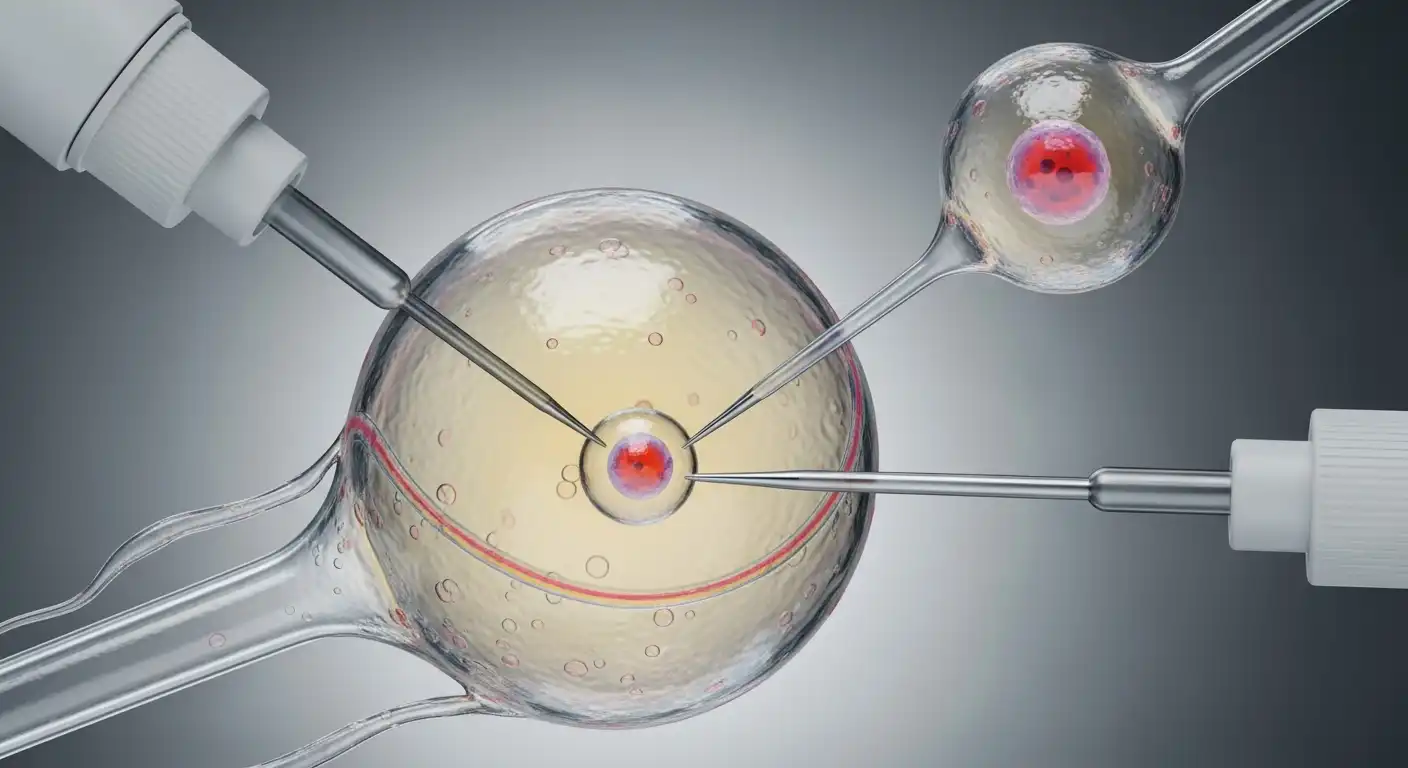

The procedure of Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer acts as a form of microscopic surgery. It requires high-precision tools and is usually performed under a powerful microscope using micromanipulators.

Step 1: Enucleation of the Oocyte

The process begins with the harvest of oocytes from a female donor (typically from ovaries collected at abattoirs for livestock cloning, or via superovulation protocols in research settings).

Once harvested, the scientist must remove the egg’s own DNA. Using a glass micropipette, the scientist holds the egg steady. A second, incredibly fine needle is used to penetrate the outer membrane (the zona pellucida) and suck out the nucleus and the polar body (a small byproduct of cell division).

The result is an enucleated oocyte—essentially an empty shell. It contains all the nutrients and energy-producing mitochondria needed to jumpstart life, but it lacks the genetic instruction manual.

Step 2: Nuclear Transfer

Next, the somatic cell (the donor) must be introduced to the enucleated egg. There are two primary methods for achieving this:

- Electrofusion: The donor somatic cell is placed next to the empty egg. An electric pulse is applied, destabilizing the cell membranes and causing the two cells to fuse. The contents of the somatic cell, including the nucleus, spill into the egg.

- Direct Injection: Using a technique similar to Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI) used in IVF clinics, the nucleus is extracted from the somatic cell and injected directly into the cytoplasm of the empty egg.

Step 3: Activation

In a natural pregnancy, the sperm not only delivers DNA but also provides an activation signal that tells the egg to begin dividing. In SCNT, no sperm is present. Therefore, scientists must artificially induce the egg to believe fertilization has occurred.

This is usually achieved through chemical or electrical activation. A jolt of electricity or exposure to chemicals (like calcium ionophores) causes a surge of calcium within the cell. This calcium surge is the biological “green light” that kickstarts cellular division.

Step 4: Reprogramming

This is the most mysterious and critical phase. Once the somatic nucleus is inside the egg cytoplasm, a battle for control ensues. The somatic DNA is formatted to be a skin cell or a liver cell—it has many of its genes turned “off.”

The proteins in the egg’s cytoplasm must remove the somatic DNA’s epigenetic marks (the chemical tags that tell the cell what to be). Ideally, the egg resets the DNA back to an embryonic state. If this reprogramming is successful, the cell forgets it was ever a skin cell and begins to act like a zygote.

Step 5: Culture and Implantation

The reconstructed embryo is incubated for several days. Scientists monitor it as it divides from one cell to two, four, eight, and eventually forms a blastocyst (a hollow ball of roughly 100 cells).

If the embryo reaches the blastocyst stage and appears healthy, it is then surgically or non-surgically implanted into the uterus of a surrogate mother. If the implantation is successful, a pregnancy ensues, resulting in the birth of a clone.

Types of Cloning: Reproductive vs. Therapeutic

It is vital to distinguish between the two major applications of SCNT, as they have vastly different goals and ethical implications.

Reproductive Cloning

The goal of reproductive cloning is to create a living organism that is genetically identical to the donor. This was the process used to create Dolly the Sheep, Snuppy the dog, and Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua (the first cloned macaques).

- End Result: A live birth.

- Primary Use: Agriculture, conservation, and pet preservation.

Therapeutic Cloning

In therapeutic cloning, the initial steps of SCNT are identical. However, the goal is not to implant the embryo into a surrogate. Instead, once the embryo reaches the blastocyst stage, scientists harvest the embryonic stem cells from the inner cell mass.

- End Result: A line of stem cells genetically matched to the patient.

- Primary Use: Regenerative medicine. Because these cells match the donor’s DNA, they can be used to grow tissues (like heart muscle or neurons) that the patient’s immune system will not reject.

Applications of SCNT in the Modern World

While human cloning remains illegal and scientifically unsafe, SCNT is actively used in several industries.

Agriculture and Livestock

This is the most commercially viable sector for cloning. Breeders use SCNT to duplicate elite livestock. For example, if a bull has superior genetics for meat quality or a cow produces record-breaking amounts of milk, they can be cloned to preserve those genetics. These clones are rarely used directly for food; rather, they are used as breeding stock to propagate superior genes into the general herd.

Pharmaceutical Production (“Pharming”)

Scientists can genetically modify a somatic cell before its use in SCNT. For instance, they can insert a human gene that encodes a valuable protein (such as insulin or blood-clotting factors) into the DNA of a goat or sheep cell. The resulting clone will be a “transgenic” animal that produces that medicine in its milk, which can then be purified for human use.

Species Conservation and De-Extinction

SCNT offers a lifeline for endangered species. If only a few members of a species remain, cloning can help increase the population and maintain genetic diversity (provided that tissue samples from unrelated individuals are available).

Furthermore, projects are underway to use SCNT for de-extinction. Scientists are attempting to edit the DNA of the Asian elephant to resemble the Woolly Mammoth and then use SCNT to create an embryo, which an elephant surrogate would carry. Similar efforts are being made for the Northern White Rhino.

Xenotransplantation

With a global shortage of human organs for transplant, scientists are turning to pigs. Using CRISPR gene editing combined with SCNT, researchers are creating pigs with organs that are “humanized” (stripped of the markers that cause immune rejection). These cloned pigs could serve as donors for kidneys and hearts, potentially saving thousands of lives.

The Scientific Hurdles: Why Cloning is Difficult

Despite decades of progress since Dolly, SCNT remains incredibly inefficient. For many species, the success rate (live births per embryo transferred) ranges from 1% to 3%.

Epigenetic Memory

The biggest barrier is incomplete reprogramming. As cells mature, they accumulate epigenetic marks (e.g., DNA methylation) on their DNA. These tags function as bookmarks, indicating to the cell which pages of the genetic instruction manual to read.

When the nucleus is transferred, the egg tries to erase these bookmarks, but it often misses some. This “epigenetic memory” suggests that the embryo may attempt to express skin-cell genes when it should be expressing embryonic genes. This leads to errors in gene expression that can cause the embryo to fail.

Large Offspring Syndrome (LOS)

Cloned animals, particularly cattle and sheep, often suffer from Large Offspring Syndrome. Fetuses grow abnormally large in the womb, leading to difficult births and health problems for both the surrogate and the offspring. This is believed to be caused by disruptions in imprinted genes—genes that regulate fetal growth and are sensitive to manipulation of the embryo.

Placental Defects

In many failed SCNT pregnancies, the placenta fails to develop the proper vascular network. This starves the fetus of nutrients and oxygen, leading to miscarriage in the first or second trimester.

Telomeres and Aging

Telomeres are the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes that shorten with age. Early fears suggested that clones would be “born old” because they inherited the adult donor’s shortened telomeres. The evidence on this is mixed. Although Dolly developed arthritis at a young age, subsequent studies of cloned sheep showed that they had normal telomere lengths (suggesting that the egg can rebuild them) and lived normal lifespans.

The Ethical Landscape

SCNT is one of the most ethically charged topics in science.

Animal Welfare

The low efficiency of the process results in many embryos being created and lost for every successful birth. Surrogates often undergo hormonal treatments and surgical procedures. Furthermore, clones that survive birth may suffer from health issues related to incomplete reprogramming. Critics argue that the suffering caused to animals outweighs the benefits in agricultural or pet cloning contexts.

The Human Cloning Ban

There is a near-universal global consensus banning reproductive human cloning. The risks of birth defects, the psychological burden on a clone (living in the shadow of the donor), and the violation of human individuality are cited as primary reasons.

However, the ethics of therapeutic cloning (creating embryos for stem cells) are more debated. Proponents argue it could cure diseases like Parkinson’s and diabetes. Opponents, particularly those who believe life begins at conception, argue that creating an embryo solely to destroy it for parts is morally wrong.

Genetic Diversity

In agriculture, reliance on cloning reduces herd genetic diversity. If all cows are clones of one “super cow,” the entire population becomes susceptible to the same diseases. A single pathogen could wipe out the entire herd because there is no genetic variation to provide resistance.

The Future of SCNT

The future of Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer lies in its convergence with other technologies.

Integration with CRISPR

The combination of gene editing and cloning is the new frontier. We are moving away from simply copying animals to “improving” them. This includes creating disease-resistant livestock (like pigs resistant to African Swine Fever) or hypoallergenic pets.

Synthetic Embryos

Researchers are exploring ways to induce somatic cells to become embryonic-like without using an egg cell (iPSCs: Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells). If perfected, this could bypass the need for oocyte donors, removing a major ethical and logistical bottleneck in therapeutic cloning.

Rescuing the Northern White Rhino

One of the most ambitious projects currently underway involves the Northern White Rhino. With only two females left (neither capable of carrying a pregnancy), scientists are using frozen sperm from deceased males and eggs harvested from the females (and closely related Southern White Rhinos) to create embryos via IVF and SCNT. This represents the ultimate test of SCNT as a conservation tool.

Conclusion

Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer is a testament to the incredible plasticity of life. It demonstrated that the destiny of a cell is not fixed; with the right biological keys, the clock can be turned back, and a skin cell can become the seed of a new life.

While the days of sensational headlines about Dolly have passed, the technology has settled into a phase of utilitarian refinement. It is quietly revolutionizing medicine through stem cell research, altering the future of agriculture through genomic preservation, and offering a sliver of hope to species on the brink of extinction.

However, the power to rewrite biological origins comes with profound responsibility. As SCNT becomes more efficient, society must continually navigate the fine line between scientific advancement and ethical boundaries, ensuring that this powerful technology serves to preserve and enhance life, rather than diminish its value.