Key Points

- Lipocartilage features fat-filled lipochondrocytes, providing unique resilience and elasticity.

- Potential applications include regenerative medicine for facial reconstruction and injuries.

- Lipids in lipochondrocytes remain stable, avoiding brittleness and enhancing flexibility.

- The study revives a discovery from 1854 and applies modern biochemical techniques.

A groundbreaking study led by researchers at the University of California, Irvine, has unveiled a new type of skeletal tissue called lipocartilage, which has significant implications for regenerative medicine and tissue engineering. Lipocartilage found in mammals’ ears, nose, and throat is unique due to its fat-filled cells, known as lipochondrocytes.

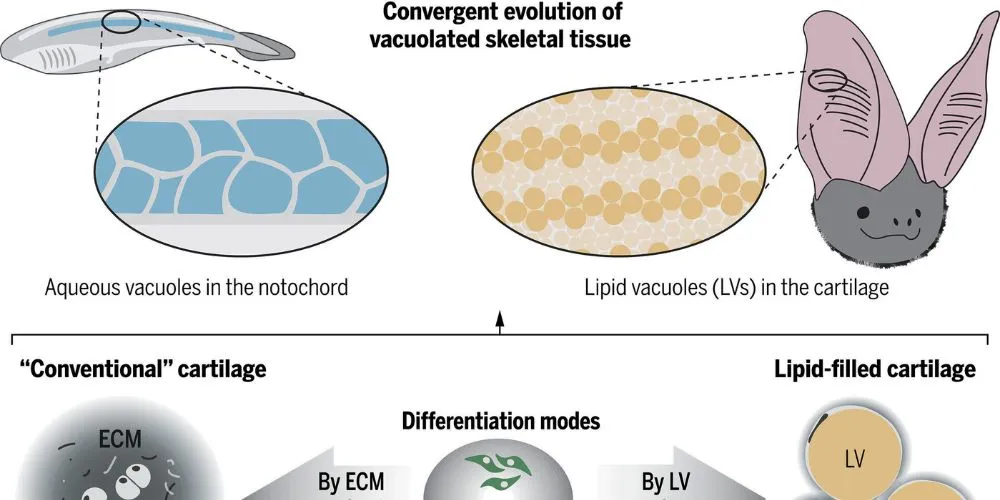

Unlike traditional cartilage, which relies on an external extracellular matrix for strength, lipocartilage derives its stability and elasticity from internal lipid reservoirs. These reservoirs keep the tissue soft and springy, similar to bubble wrap, while maintaining remarkable resilience.

Published in Science, the study highlights that lipochondrocytes differ from ordinary fat cells by maintaining constant size regardless of food availability. This stability makes lipocartilage ideal for reconstructive applications, particularly for flexible body parts such as earlobes and noses.

Maksim Plikus, a professor at UC Irvine and the study’s corresponding author, noted that this discovery could revolutionize cartilage reconstruction, reducing the need for painful procedures like rib cartilage harvesting. Future advancements may allow patient-specific lipochondrocytes to be derived from stem cells and shaped using 3D printing to treat facial defects, injuries, and cartilage-related diseases precisely.

The discovery also revives a long-overlooked finding by Dr. Franz Leydig, who first identified fat droplets in rat ear cartilage in 1854. Modern techniques have now detailed lipocartilage’s molecular biology, metabolism, and structural role in skeletal tissues.

Researchers revealed genetic mechanisms that lock lipid reserves in lipochondrocytes by suppressing enzymes that break down fats. Without these lipids, lipocartilage becomes brittle, underlining the critical role of fat-filled cells in maintaining flexibility and durability.

Additionally, the team observed intricate arrangements of lipochondrocytes in certain mammals, such as bats, where they form structures that may enhance hearing. Lead author Raul Ramos emphasized that this discovery challenges established notions in biomechanics and opens new pathways for exploring cellular stability, aging, and lipid applications in medicine. The collaborative study, which involved experts from across the globe, highlights the vast potential of lipocartilage in advancing biomedical science.