Key Points

- A new, faster, and cheaper method for single-cell genetic sequencing has been developed.

- The technique uses thousands of tiny “micro-bubbles” and DNA barcodes to increase throughput dramatically.

- A key advantage is that it is “size-agnostic,” allowing scientists to sequence everything in a sample, regardless of its size.

- In a real-world test, the method discovered an abundant family of viruses that would have been invisible to other techniques.

A new method is set to dramatically improve single-cell genetic sequencing, enabling scientists to read the genomes of individual cells and viruses faster, more efficiently, and at lower cost.

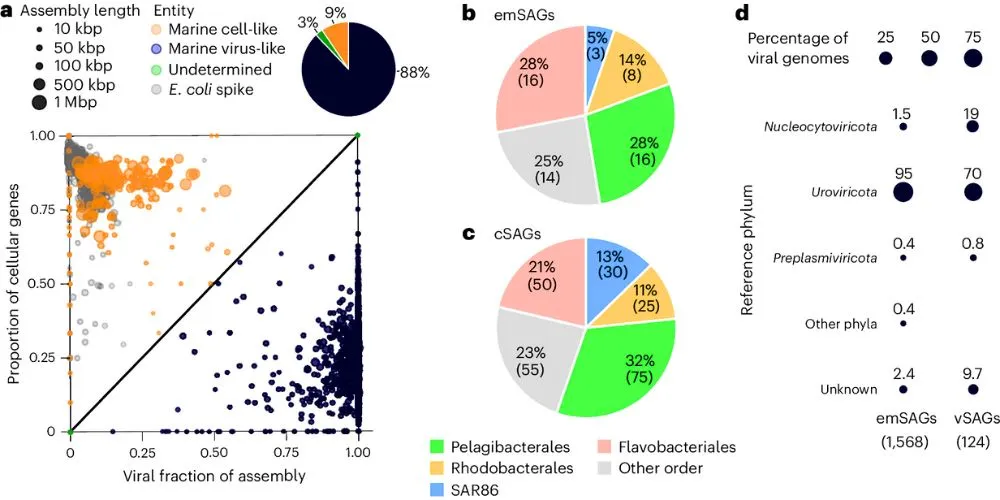

In a study published in Nature Microbiology, researchers from Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences and Atrandi Biosciences detailed the first real-world use of this new approach, which they call “environmental microcompartment genomics.” By sequencing the microbiome in a seawater sample from the Gulf of Maine, the team showed just how much better the new method is than traditional methods, especially for studying the complex world of marine viruses.

The traditional method, which was pioneered at Bigelow Laboratory, sorts individual particles into 384 separate wells on a microplate. The new approach increases the output by a huge margin. In the study, researchers sequenced over 2,000 particles from a tiny seawater sample—less than a millionth of a liter.

The new method uses recent advances in microfluidics. A sample is broken down into thousands of tiny, semipermeable bubbles, each containing a single cell or virus. Inside each bubble, the DNA is copied many times and then tagged with a unique barcode. When the bubbles are dissolved, that barcode allows scientists to perfectly stitch the corresponding DNA sequences back together into a complete genome.

A major advantage of this technique is that it doesn’t require any pre-sorting by size. This means it can sequence anything in a sample—from large microbes to the smallest viruses and even free-floating DNA—at the same time.

“This approach omits any size selection so that we can process everything… simultaneously,” said Alaina Weinheimer, the study’s lead author. “You’re looking at the microbial community in a very holistic way.”

This proved critical in their study. The new method identified a whole family of viruses, called Naomiviridae, with an unusual DNA structure that other methods would have missed.

“This group of viruses was the most abundant in our dataset… but we would have missed it entirely with other methods,” Weinheimer said. “We’re showing that there’s a lot that can still be discovered… that we’re starting to unlock with these new methods.”